Bowen Research Fellow Completes Tenure in Sub-Saharan Africa

During any given academic year, some professors teach, while others prepare for courses in new subject areas. Still others focus on public service projects, while their colleagues work on research projects tied to their specialty areas. Ideally, professors at the UALR William H. Bowen School of Law work in all these areas – sharing their passions and scholarship in the classroom to enrich their students’ experiences and shape futures.

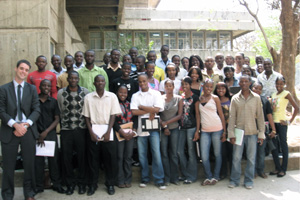

New NGO to Focus on Justice: On his most recent trip to Zambia, Nick Kahn-Fogel helped form an NGO to address issues with access to justice in the small country.

Bowen Visiting Assistant Professor Nick Kahn-Fogel focused on each of these areas while he served in Zambia during the past academic year as a Bowen Research Fellow.

As a result of his tenure there, the professor wrote two papers that have been accepted to major journals. One is on the shortage of lawyers in sub-Saharan Africa – forthcoming in the University of Pennsylvania Journal of International Law – and one focuses on the analysis of eyewitness law for the University of Alabama Civil Rights and Civil Liberties Law Review. Another work on the colonial influence on human rights development in Africa is in progress.

However, Kahn-Fogel’s work in Africa went miles beyond simply writing about problems inherent in the Zambian justice system. Instead, he worked to educate future lawyers in the University of Zambia and form a public-service organization focused on improving access to justice in the still-developing democracy.

Access to Justice

The concept of access to justice is directly tied to how many individuals perceive democracy in action. Without one, there cannot truly be the other. Yet, in many new countries, establishing a system of courts and training individuals to work in them can be one of the most daunting tasks possible.

The Republic of Zambia gained independence from Britain in 1964, and after years of rule under a one-party state, established a multi-party democracy in 1991. Despite a more stable economy, growth in the country’s gross domestic product, and increased trade, Zambia still only has one attorney for every 18,000 citizens.

Compare that number to the one attorney per 300 individuals in the United States. One can then begin to see the issues involved in establishing a justice system for almost 13 million people in a country only slightly larger than the state of Texas.

Free video maker | Create your own video easily

Create and share videos for free with Animoto’s video maker. Combine your photos and video clips with music to make professional videos that’ll impress.

These statistics were only one of the reasons that Kahn-Fogel decided to spend 2006 through 2008 at the University of Zambia as a lecturer in the school of law. A family friend’s experience as a professor and dean in the country helped Kahn-Fogel determine that he could make a difference in the lives of law students there.

“After graduating from law school, I thought it was important to use my degree in a worthwhile fashion,” Kahn-Fogel said. “The country needs more attorneys, and those lawyers need more training. I thought I could do whatever they needed, but I didn’t know exactly what it would be like.”

During his first visit to Zambia, Kahn-Fogel lectured in torts and intellectual property and conducted tutorials on Zambian constitutional law for undergraduate law students. The school is run in the British fashion, where students listen to lectures in large groups and then engage in smaller seminars.

“As my first teaching job, it was a wonderful experience,” Kahn-Fogel said. “I was also able to do research into comparative criminal procedure as well as teach.”

But the professor noticed a problem with the system of educating lawyers. While between 80 and 100 students graduated each year, a much smaller percentage passed the bar after another year of postgraduate study.

“The post-graduate bar admissions program is much more academic than what was originally envisioned in Zambia,” Kahn-Fogel said. “Originally, it was conceptualized as a program that would replicate a clinical environment for recent law graduates. Now, those who teach the bar admissions courses are still primarily clinicians, but they are teaching in a more traditional, academic lecture format, , which they’re not necessarily trained to do.”

In addition to issues with the structure of the post-graduate program, problems with effective feedback for students exist. A student has three chances to pass every portion of the local bar exam. If he or she does not succeed, a five-year waiting period is imposed. The student only knows which portions of the exam he or she has passed. Errors on the failed portions are never explained.

“There is a dramatic scarcity of resources for education among the general population,” Kahn-Fogel said. “It was a part of the colonial legacy that higher education among the indigenous population was discouraged. At the time of Zambian independence, only 100 indigenous Zambians were college graduates.

“There was not one single Zambian attorney in the country.”

These inequities continued, despite Zambians’ new access to higher education in the new democracy. Problems with access to quality training for attorneys stem, in part, from the likelihood that law teachers must spend time working in their own practices. Their attention can be divided, given the strong economic incentives to seek extra work outside the academy.

Possibilities for Reform

Kahn-Fogel sees opportunities for restructuring the system of legal education in Zambia, but he knows that the country has many challenges ahead. He was so inspired to seek out solutions to the problem that he worked with Zambian attorneys to establish a non-governmental organization (see Sidebar) to focus on this issue.

Two possible areas of improvement are allowing the use of contingency fees, because the current prohibition on that payment structure precludes most of the population from hiring lawyers.

“We see that there needs to be a reform of the law-education process in Zambia and there need to be greater incentives for law school faculty to fulfill their teaching obligations,” he said. “The problems Zambia faces, unfortunately, are common throughout much of the continent.