There is always something magical about seeing the bright flash of a meteor as it streaks across a dark, star-filled sky. One moment you are gazing upwards, admiring the view of the “fixed” stars upon the dome of the sky, when, suddenly, from out of nowhere, a tiny bit of rubble left behind from a passing comet, punches through our planet’s atmosphere only to go out in a sudden blaze of fiery glory right before your eyes. It’s as if the universe is letting you know, ever so subtly, that the ball of spinning rock you are standing upon exists within a much larger context. More often than not, our sighting of a meteor is usually restricted to the occasional sporadic space rock zipping across the night sky, but, on certain nights throughout the year, we get treated to the opportunity of seeing more than just one or two. For it is on these handful of special nights that we get treated to a meteor shower!

WHEN AND WHERE TO LOOK

First off, I should inform you that the April Lyrids is not one of our most productive of meteor showers. In fact, count yourself lucky if you see 15 per hour during the peak hours. The average rate is about 10 to 20 meteors per hour. Why am I highlighting an otherwise low-producing meteor shower? Because sometimes, on rare occasions, the Lyrids will cut loose with a veritable rain of meteors. In the year 1803, stargazers saw more than 500 meteors per hour. The years 1849, 1850, 1884, 1922, and 1982 also saw more meteors than normally associated with the Lyrids. Will this year be one of those more productive years? Probably not, but then again, you never can tell. But that’s part of the fun of a meteor shower, sometimes you end up being disappointed and other times you might end up being pleasantly surprised. The thing is, you won’t know if you don’t look.

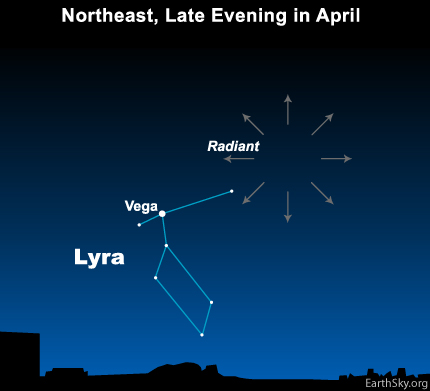

The Lyrids peak during the early morning hours of Sunday, April 22nd (which also happens to be Earth Day) but you can expect to see meteors off and on from about April 16th through April 25th. Meteor showers get their name from the constellation they appear to radiate from in the sky. In other words, even though you can see meteors shooting across any part of the sky, if you were to map them out and trace back where they appear to originate from, then you would see that that point is centered upon a particular constellation. I stress the word “appear” because the constellation and the shower are of course not physically linked in any way. The radiant for the Lyrids is, you guessed it, in the constellation of Lyra. At this time of the year, Lyra does not rise in the northeastern sky until around midnight and this is why you won’t see many meteors until after 12:00 A.M. As the constellation climbs higher up in the sky your chances of seeing more meteors gets better and better but it won’t reach its highest point until near dawn and that happens to be the peak hours for this meteor shower.

This year we are lucky in that the quarter moon will set in the west during the early evening, so its glare will not interfere with your observing. But you will still need to observe from a location with as dark a sky as possible in order to see the most meteors and this generally means getting out of the city. I’m often asked about where to go here in the city to observe meteor showers. One place I might suggest is the Nature Conservancy’s Ranch North Woods Preserve off of Highway 10 and located at 8803 Ranch Blvd. The Nature Conservancy encourages the use of the facility for such things, but I urge you call them at (501)-663-6699 to confirm and to let them know that you would like to use the site for meteor shower observing. A good rule of thumb for whether or not your sky is dark enough is to see if you can spot all seven stars that form the Big Dipper.

To sum up: Your best night for observing will be on April 22nd from midnight until dawn. Expect to see meteors in any part of the sky but remember that the radiant starts out in the northeast after midnight and then climbs higher up in the sky as the evening progresses until finally culminating in the western part of the sky at dawn. Dark skies will always be your best friend. Oh, and no special equipment required, your unaided eye, some caffeine, warm clothes, reclining lawn chairs or a blanket on the ground, snacks, and a group of friends or family will all make things more comfortable and more fun.

WHAT YOU ARE SEEING

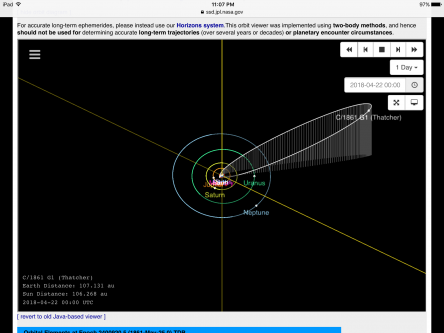

The Lyrids have a very long history, going as far back as 687 BC according to records that we have from a Chinese astronomer of that time who wrote “at midnight, the stars dropped down like rain”. They likely go even further back in time than this. The parent body source for the Lyrid meteors is Comet Thatcher, first discovered in 1861 by a New York amateur astronomer named A.E. Thatcher. Comet Thatcher is what is known as a long-period comet, comets that take 200 years or more to orbit the Sun. Thatcher takes 415 years to make such a trip. Its last appearance was in the year of its discovery in 1861 and it will not be back again until the year 2276.

The Lyrids have a very long history, going as far back as 687 BC according to records that we have from a Chinese astronomer of that time who wrote “at midnight, the stars dropped down like rain”. They likely go even further back in time than this. The parent body source for the Lyrid meteors is Comet Thatcher, first discovered in 1861 by a New York amateur astronomer named A.E. Thatcher. Comet Thatcher is what is known as a long-period comet, comets that take 200 years or more to orbit the Sun. Thatcher takes 415 years to make such a trip. Its last appearance was in the year of its discovery in 1861 and it will not be back again until the year 2276.

At aphelion, its most distant point in its orbit, Comet Thatcher is around 110 Astronomical Units (AU) from the Sun. One AU is equivalent to the average Earth-Sun distance of 93 million miles. At perihelion, its closest point in its orbit, Comet Thatcher is 0.9207 AU’s away from the Sun. It’s when it is making its perihelion run that Comet Thatcher begins to heat up from the Sun’s energy and parts of it begin to vaporize, creating long rivers of comet dust in space. When the Earth plows through this leftover debris, we get a meteor shower.

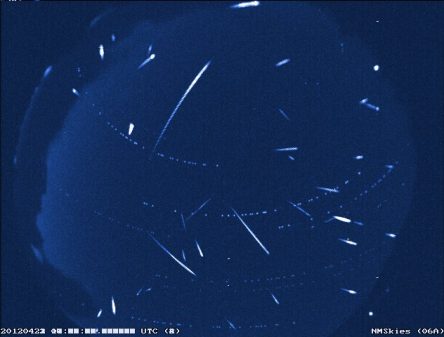

Lyrid fireball photo by Sam Cornwell

Meteor Fireball Breakup photo by Chumack

Most of this comet dust is no bigger than a grain of sand but when it enters the Earth’s atmosphere it is traveling at around 105,000 mph, much faster than NASA’s Voyager 1 spacecraft, the fastest man-made object in our solar system, traveling at the current rate of 38,000 mph. When the grain of sand-sized material slams into the atmosphere at that speed, it suddenly compresses a column of air out ahead of it. This in turn heats the column of air up to several thousand degrees Fahrenheit, ionizing the gases and making them glow. It is also so hot that the incoming bit of comet dust is completely vaporized. Every now and again there are pieces of Comet Thatcher hurtling through our atmosphere that are a bit bigger than a grain of sand. This larger material can produce Lyrid fireballs, meteors that are brighter than a magnitude of -4, as bright or brighter than the planet Venus (currently visible in our western sky after sunset). Lyrid fireballs can be so bright they may briefly cast shadows and leave behind visible smoke trails that linger for several minutes.

What do you do if there are clouds? Check to see if there are any livecast shows of the meteor shower. Oftentimes web sites like Slooh.com, various observatories, and even NASA will have live coverage of meteor shower events. But nothing beats seeing a meteor shower with your own eyes. It affords you the chance to feel connected to a universe vast beyond comprehension as well just spending a little time outside with your friends and family. Get outside and look up!