by Chad Garrett, director of technology

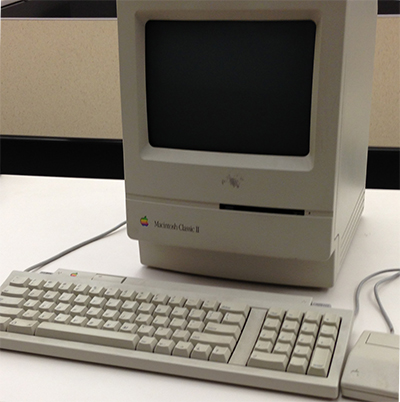

When I got my first IBM-compatible computer in the late 1980s, it had two 5.25-inch floppy disk drives. One drive held a program disk, the other a disk with my data. I didn’t do any game-changing work. Mainly I wrote papers for school using a proprietary word processing program and explored my creative side designing flyers and posters with The Print Shop. By the time I was an undergraduate, I was using a Mac Classic II in the university’s writing center and saving my work on 3.5-inch floppy disks. Lots of 3.5-inch floppies.

A flashback to writing papers as an undergraduate

In the years since, I’ve found myself saving external copies of my files on Zip disks of varying sizes, CDs, DVDs, at least one Blu-ray disc, external hard drives, and flash drives. And of course there are the hard drives on the many computers I’ve used and now the cloud storage services that make my digital life pretty easy. But what would happen today if I tried to trace my high school experience back through those 5.25-inch floppies from the late 80s? When was the last time I saw a computer at Best Buy with a 5.25-inch disk drive in it? And even if I found an old computer with a working disk drive, I’d have to cross my fingers and test to make sure the disks on which I saved my files had not degraded or been damaged. Then I still wouldn’t be out of the woods because I would face the challenge of trying to figure out how to open files created in proprietary formats by programs (and versions of programs) that are no longer available.

This is a dilemma faced by archives around the world that are tasked with preserving history in the digital age. The National Digital Stewardship Alliance (NDSA) aims to help address that dilemma. A consortium of institutions committed to the long-term preservation of digital information, the NDSA’s mission is to establish, maintain, and advance the capacity to preserve our nation’s digital resources for the benefit of present and future generations. Today, I was thrilled to be attending the annual meeting of NDSA partner institutions in Washington, DC, when the NDSA released its inaugural National Agenda for Digital Stewardship. The agenda serves to inspire and guide institutions to commit themselves to digital stewardship. The opening paragraph boldly explains the need for such stewardship:

Our culture is a digital culture. The photographs of our families; the electronic communities where we share and receive news; the maps that give us new insight on where we’re going and how to get there; the films and music that shape our shared experiences—all digital. Our digital creations represent an incalculable investment in time, energy, and resources that requires responsible care to remain viable over time.

The agenda authors claim that a lot of work needs to happen in order to ensure our valuable digital content today remains accessible, useful, and comprehensible in the future. Often we think only about our own personal digital lives (our digital photos, music, iPhone videos, and so forth), but the digital culture reaches far beyond us as individuals, and into our government, universities, libraries, cultural heritage institutions, and civic and religious organizations. Consider as an example the number of Facebook pages for organizations or movements each of us has liked. Archives have always existed to support a thriving economy, a robust democracy, and a rich cultural heritage, but the tasks facing archives in the digital age are more daunting and complex than ever.

We do have a lot of work to do. At the Center for Arkansas History and Culture (CAHC), we are in the early stages of developing our digital preservation strategy and processes. Yes, we’ve found some surprises in our collections like the 8-inch floppy disks from the unprocessed Frank White Papers. We have also found an impressive number of 3.5-inch floppies and CDs. The contents of these media vary from image files and Microsoft Word documents to files created by software that is no longer available. Our job is to ensure that the contents of these media—rather than the media itself—are preserved and accessible well into the future.

I’ve learned a lot in the short time that I’ve worked with archivists. One of the most important lessons is that the job of archives is to preserve the past and present for future generations. Archives don’t dictate what the future sees of the past. They simply strive to preserve what they can so that people 200 years from now can both interpret and understand what happened today.