August Feature – The Lagoon Nebula (Messier 8) & Trifid Nebula (Messier 20)

August is a perfect time to observe the summer Milky Way, that band of pale, ghostly light arching across the sky from the stinging tail of Scorpius in the southwest, right through the celestial swan flying high overhead, and then back to the northeastern horizon where Cassiopeia sits, tilted at a crazy angle, upon her throne of stars. That band of soft, pale light that we call the Milky Way is the combined glow of millions of distant suns embedded within the disc of our home galaxy and too far away to be seen as individual stars.

Mixed in with all the stars and ghostly light are vast clouds of interstellar gas and dust, the raw material from which new stars are made. Exploring the length and breadth of the Milky Way with binoculars or telescopes (and even with the unaided eye) an intrepid stargazer will find a multitude of deep-sky treasures to savor; including a variety of star clusters, pitch-dark clouds of gas and dust, as well as glowing clouds of star stuff, places where new stars are being born. Summer stargazers are especially fond of visiting two stellar nurseries: The Lagoon Nebula (Messier 8) and the Trifid Nebula (Messier 20). So, let’s dive into the Lagoon and begin our exploration of these two celestial gems.

WHEN AND WHERE TO LOOK

Step outside on a clear, dark August evening and face towards the SSW, making sure that you have a good, unobstructed view of the horizon. Locate the distinctive outline of the constellation Scorpius (use a sky map obtained from the internet or from an astronomy magazine or an app) as the giant arachnid lays upon its side against the southwestern horizon. Just to the east of Scorpius’ tail, and positioned a little higher up in the sky, is the constellation of Sagittarius.

Sagittarius is said to represent a centaur archer but if you can see that within this grouping of stars then you have a much better imagination than most people. Far more recognizable than a half man/half horse armed with a bow and arrow is a pattern of 8 second magnitude stars resembling a teapot. In fact, this asterism (an unofficial star pattern made from the stars of one or more constellations) is indeed called, “The Teapot”. It may take you a minute or two to see the pattern but once you do you will immediately recognize the handle, lid, body, and spout. The Teapot looks as though it is tilted a bit westwards, perhaps about to pour a nice, piping hot cup of tea. If your skies are dark enough then you will see the pale, white light of the Milky Way rising like steam from the spout. The Milky Way is especially bright around this part of the Teapot as we are gazing off into the direction of the dense and busy center of the Galaxy.

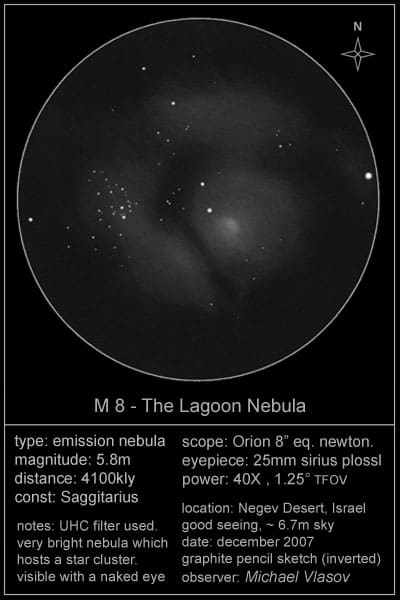

Locate the star Nunki in the Teapot’s handle and the star Kaus Borealis that forms the very top of the pot’s lid. Draw an imaginary line in between these two stars, now extend that line for the same distance in a westerly direction. At the end of the line you will be right around the general area of M8. If your skies are dark enough then you should see it as a faint, fuzzy patch of light upon the sky. Binoculars will reveal M8 as a softly glowing cloud with a few bright stars scattered around. Small telescopes will show more glowing nebulosity and clusters of glittering stars separated by a dark divide of dust (the “lagoon” of the nebula). Larger aperture scopes reveal even more details.

M20 is just two degrees to the northwest of M8. In binoculars, M8 appears as a small, fuzzy blob of light. A small telescope will reveal the nebula as a circular patch and, if your skies are sufficiently dark, you should begin to see the dark dust lanes that appear to divide the nebula into three lobes. By the way, the name “Trifid” is pronounced “try-fid” (meaning: to divide into three sections) and not “Triffid”, which is pronounced “triff-id” and is the name of the famous plant-like aliens in John Wyndham’s classic sci-fi novel, “The Day of the Triffids”. In large aperture scopes (8 inches or more), the dust lanes become even more pronounced.

NOTE: using a UHC filter (a narrowband light filter) may bring out more contrast and details in M8 and M20. I would suggest using low magnifications for M8 given its large size (its apparent size is 3X that of the full moon) while M20 will fare better under slightly higher magnifications.

WHAT YOU ARE SEEING

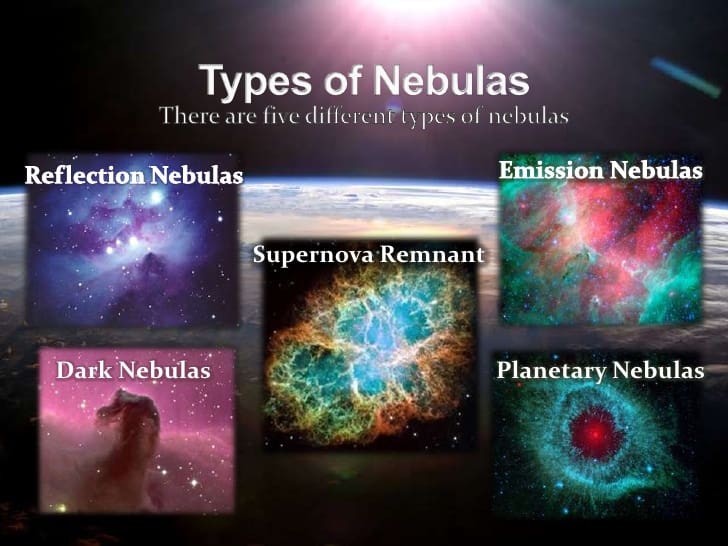

There are three primary types of nebulae (clouds of interstellar gas and dust). Two of them are associated with star death while the other is linked to star birth.

Planetary nebulae have nothing to do with planets, early observational astronomers dubbed them this because, through a telescope, many of them resemble a planet-like disc. The name has stuck ever since. These nebulae are made when stars much like our own sun are in the late stages of their evolution and have blown off shells of gas that expose the white-hot core of the star. Intense radiation from the now exposed core excites the gas shells and makes them faintly glow.

Supernova remnant nebulae are the residual clouds of gas and dust left over from when massive stars die in violent supernova explosions.

Gaseous nebulae are dense concentrations of cold, molecular hydrogen and dust from which stars are being born, or are yet to be born.

There are three types of gaseous nebulae:

- Dark nebulae are dense clouds of gas that are yet to produce stars and, so, they appear as dark blobs or patches in the sky.

- Emission nebulae are clouds that contain hot, young stars and shine because their radiation is making the clouds glow.

- Reflection nebulae are clouds that contain hot, young stars and shine because they are reflecting the radiation from the stars within.

Located some 4,310 light years away and spanning 9 light years across, M8 is both an open star cluster and an emission nebula that is still in the process of creating newborn stars. It is one of only two star forming regions visible to the unaided eye here in the northern hemisphere, the other being the Orion Nebula (Messier 42). The clouds of gas and dust are highly ionized (electrons are being stripped from atoms) by the intense radiation of hot young stars such as Herschel 36 and 9 Sagittarii which are embedded within the nebula. When imaged by the Hubble Space Telescope astronomers could see that the radiation and stellar winds from stars like Herschel 36 have shaped parts of the nebula into half-a-light-year-long tornado-like structures.

The open star cluster within the nebula is NGC (New General Catalog) 6530, it consists of about two dozen stars that are approximately 2 million years of age. Still pups by cosmic standards.

M20 is some 2,660 light years away, with a diameter of 15 light years. The age of M2 is placed at around 400,000 years, half again as old as Homo sapiens, which is thought to be about 200,000 years old.

M20 is a mix of open star cluster as well an example of an emission, reflection, and dark nebulae. The most distinctive feature of M20 are those dark nebula lanes that divide it up into those three sections, although photographs will reveal 4 lobes. Photos also reveal the nebula to have a pink glow, this is the color produced by the ionized hydrogen atoms that are being energized by hot, young stars. Pink being the color given off by ionized hydrogen atoms. This is what creates the emission nebula.

Adjacent to the pink nebula is a blue nebula. The blue is produced by the light of these young stars reflecting off dust grains inside the nebula, with the bluer portions of the star’s light being reflected more efficiently than the red portions of the spectrum.

The open star cluster within M20 is composed of a loose assortment of about 50 stars, a dozen of which can be seen with small backyard telescopes.

Fans of the original Star Trek series may recall the episode, “The Alternative Factor”, in which M20 is hinted at as being the gateway to another dimension.

M8 and M20 are best placed for viewing in our sky from late summer to mid-fall. Armed with a good sky map and some modest optical aid, you too can find deep-sky treasures like these all along the summer Milky Way. Get outside, look up!