April 2021 Feature – April Showers: A Look at the Lyrid Meteor Shower

The sight of a meteor streaking across the starry vault overhead never fails to elicit ‘ooohs’ and ‘ahhhs’ from stargazers of all ages and experience levels. It truly is a magical sight to behold and the memories that can be had from such experiences sometimes last us a lifetime. Especially when shared with those we love. This month brings us a rather modest meteor shower but one that is still well worth your time to get out and enjoy, especially given the unpredictable nature of this particular celestial event.

WHEN AND WHERE TO LOOK

The Lyrids begin to show themselves around April 16th and they will linger around until about April 30th but the peak time of their activity will occur on the night of April 21st and into the early morning hours of April 22nd. Begin looking at around midnight on the 21st and expect to see the most meteors (10-15/hour) during the predawn hours of the 22nd.

The shower gets its name from the constellation of Lyra. In Greek mythology, the constellation is said to represent the lyre (a harp-like musical instrument) of Orpheus, the man who dared to enter Hades itself in order to bring back his true love, the beautiful Eurydice. As with many such tales in Greek mythology, the story ends in tragedy. Anyways, if you were trace back upon the sky the origin of a meteor on the peak night, and found that it seemed to originate around Vega, the brightest star in Lyra, then you were indeed seeing a Lyrid. But these meteors really have nothing to do with Vega or Lyra, it’s just a line-of-sight effect. In order to know where they really come from, read on! But the bottom-line thing to know right now is that even though Lyrids all appear to radiate from a single point upon the sky, you can expect to see them zipping by in any direction you look, so don’t worry about focusing your attention exclusively on Lyra, which rises in the NE shortly before midnight right now.

WHAT YOU ARE SEEING AND HOW TO SEE IT AT ITS BEST

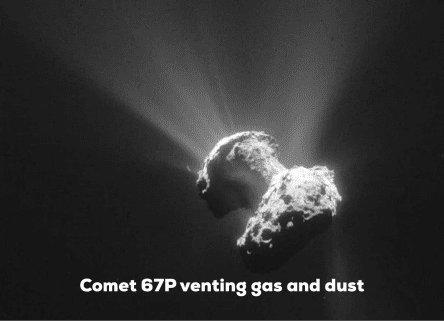

As with the vast majority of all of our meteor showers, the Lyrids are the result of the Earth plowing through comet dust. For some 2,700 years, people have been observing Lyrid meteor showers every April and the reason that they do so has to do with Comet C/1861 G1 (Thatcher). Comet Thatcher is a dirty snowball from the outer edges of the solar system that passes our way once every 415.5 years. The comet was first discovered in 1861, the last time it was in our area, by A.E. Thatcher, whose name the comet now bears. We know its orbital path pretty well and can trace back its previous visits for thousands of years. Each time it ventures into the inner solar system, the Sun warms its icy exterior and the comet vents dust and ice particles out into space, forming trails that are millions of miles long. These trails of ice and dust linger for eons and whenever the Earth plows through one, the particles burn up in our atmosphere, creating the spectacle of a meteor shower.

Now when I say that this stuff is made up of icy dust, I’m not kidding. Those bright streaks of light that you see upon the sky were actually created by something no bigger than a grain of sand (maybe pea-sized in some cases). Whaaaa? How can that be? Lyrid meteors may be the result of sand grained-sized comet fluff but you must keep in mind one thing: speed. These things are slamming into our atmosphere at some 110,000 mph. Zoom-zoom! If you want to get technical about it, the kinetic energy of an object (the energy derived from its motion) is proportional to its mass multiplied by its velocity squared. In other words: a grain of ice moving at 110,000 mph has a heck of a lot of energy associated with it. As it slams into the atmosphere, it compresses a column of air out ahead of its direction of motion, converting that kinetic energy into heat and light. This violent and suddenly shocked column of air heats up to thousands of degrees Fahrenheit, glowing briefly as a meteor streak and totally vaporizing the ice/dust grain. And that, boys and girls, is a meteor.

On average, most of the Lyrids that you see will be about as bright as the stars in the Big Dipper. Not bad, but really around middling brightness. What you will want to keep your eyes peeled for are fireballs. Lyrid fireballs are created by pieces of material a little bit bigger than a grain of sand and they can be as bright, or brighter, than the planet Venus. For a split second, you may notice that they are bright enough to even cast shadows. If you see one, look for smoky debris trails that can linger around in the sky for minutes afterwards.

Now I don’t want to get anyone’s hopes up but, it is possible that the Lyrids could cut loose from their typical 10-15 meteors per hour to 90 or 100 per hour. Whoa, settle down now, this is far from a sure thing, but it has happened before and it’s very hard to predict when it might happen again. Just know that there is historical precedence for such things and that it’s a reason why you shouldn’t gloss over the Lyrids, they are just so darned unpredictable. It’s what makes meteor shower observing so exciting. More often than not you won’t see much but if you stay inside, you won’t see anything at all. The last time the Lyrids put on such a show was back in 1982 and we have an interesting newspaper account from 1803 by a journalist in Richmond, VA who witnessed such a spectacle (keep in mind that folks did not yet know the origins for meteor showers at that time):

“Shooting stars. This electrical [sic] phenomenon was observed on Wednesday morning last at Richmond and its vicinity, in a manner that alarmed many, and astonished every person that beheld it. From one until three in the morning, those starry meteors seemed to fall from every point in the heavens, in such numbers as to resemble a shower of sky rockets…”

Holy Meteor Mania, Batman, I would have loved to have seen such a display! Alas, there are no expectations for this year’s Lyrids to put on such a show but then, you never really know.

As with any meteor shower, you will get the best results if you observe during the peak times and, most importantly, from a dark sky locale. As you all know, we have deprived ourselves of the joys the night sky has to offer by lighting up our nighttime environment in the most inappropriate ways. Finding a dark sky observing spot can be a challenge but to help you out,

visit the Arkansas Natural Sky Association for safe, public sites near you (https://darkskyarkansas.org).

Get comfortable, you don’t want to strain your neck peering around the sky. Put blankets or sleeping bags down upon the ground or lay in a comfortable reclining lawn chair. Dress weather appropriately and be sure to have layers of clothing that you can take on or off. Bring along insect repellant and plenty of snacks and beverages. Let your eyes get adjusted to the dark and refrain from using your cell phone or tablets as the light from these devices will ruin your night vision. Likewise, avoid the use of flashlights unless they have a red LED setting. Red light is less harmful to your night vision. You can also use red film over a white flashlight to achieve the same result. Finally, be patient. We call these events “showers” but that does not mean that they are going to fall out of the sky like rain. And have fun. Take along a friend or two. Better yet, take along someone you love. These moments are for creating memories with people you care about, even if you don’t see anything, you will have at least spent time in the company of someone special to you. Enjoy, and always remember to look up every now and again to the awe and wonder of our night sky.