April 2019 Feature – Cor Caroli, The Heart of Charles

Oftentimes you will hear that “the Sun is an average star”. But that really isn’t meant to be taken in the strict mathematical sense of “average”. For example, the most abundant stars within our galaxy are what’s known as “red dwarfs”. These are stars that are far less massive than the Sun. They range from 0.075 to about 0.50 solar masses, have surface temperatures much cooler than the Sun’s 5778K, and make up about 70% of the stellar population within the Galaxy. Clearly, in this regard, the Sun is not an “average star”. When astronomers say that the Sun is average, what they really mean is that there is nothing exceptional about it. Like most stars in the prime of its life, it is still happily fusing hydrogen within its core and still has many years ahead of it.

But in one regard, our neighboring star does stand out from many others: it’s alone. The majority of stars in our galaxy are actually double, or multiple, star systems, where the stellar components are all gravitationally bound together and orbit around a common center of mass. From within the vast clouds of cold, molecular hydrogen gas and dust that are found throughout the arms of the Galaxy, stars are born in litters of dozens, hundreds, or even thousands. As they disperse from their stellar nurseries, many of them leave the cradle accompanied by siblings, but our Sun appears to be the exception. This month, we are going to take a look at a binary pair of stars that, collectively, goes by the name of Cor Caroli, Latin for “Heart of Charles”.

HISTORY AND MYTHOLOGY

So, who is this guy Charles that gets a star named after him? Well, that’s not entirely clear. It’s either King Charles I of England (executed for high treason at the end of the second English Civil War in 1649) or his son, King Charles II (proclaimed king in 1660 upon the restoration of the monarchy). According to some sources, it was Sir Charles Scarborough, personal physician to Charles II, who gave it the name of Cor Caroli, The Heart of Charles. Scarborough was said to have noted that when Charles II returned to England in order to be crowned, that the star was shining with a definite new brilliance. Color me skeptical of Sir Charles’ claims.

Yet another source says the star did not get its name until 1725 when Sir Edmund Halley (discoverer of Halley’s Comet) decided to commemorate Charles II with the honorific. There is no historical verification of this, however. During the late 1970’s, Deborah Jean Warner, of the Smithsonian Institute, said that the name was actually meant to honor Charles I.

Who is right? Well, more recently (1989), British astronomer Ian Ridpath noted that the first known use of the name was actually from a star map created in 1673 by Francis Lamb and that the full name was “Cor Caroli Regis Martyris” (“the heart of Charles, the martyred king”). This of course would strongly support the theory that the name was intended to honor Charles I.

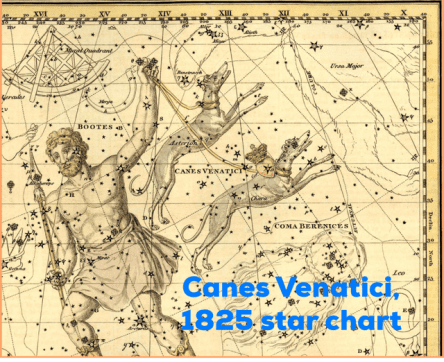

Cor Caroli belongs to the small constellation of Canes Venatici. According to myth, the constellation is said to represent the two hunting dogs of Bootes (pronounced: Boh-oh-tees, NOT Boot-ees), the herdsman. The two brightest stars in this constellation are Cor Caroli, shining with an apparent magnitude of 2.84 to 2.98, and Beta Canum Venaticorum, with an apparent magnitude of 4.26. Like any good dog owner, Bootes gave his canine pals names. Cor Caroli represents where his dog Chars would be located while Beta Canum Venaticorum is the space occupied by Asterion.

HOW TO FIND COR CAROLI

Locating Cor Caroli is quite easy, just look beneath the handle of the Big Dipper, it’s located about 17 degrees to the south of the star Alioth (the star in the dipper’s handle that lies closest to the bowl).

THE SCIENCE OF COR CAROLI

Some of the double stars you see in the night sky are what’s known as “optical binaries”, stars that look like they are close together due to a chance alignment along our particular line of sight. Cor Caroli however is a true binary, two stars that are interacting gravitationally with one another and that orbit around a common center of mass.

Best estimates place this binary pair at around 110 to 120 light years away and the two are separated from each other by about 650 to 670 Astronomical Units (one Astronomical Unit, or AU, is the equivalent of the Earth/Sun distance of 93 million miles), and it probably takes almost 8,000 years for the pair to complete one orbit around each other.

The brighter component is known as Alpha-2 Canum Venaticorum (which uses the genitive , or possessive form, of the constellation’s name, a common practice when talking about many of the stars belonging to a given constellation). Astronomers classify stars based upon their surface temperatures utilizing an alphabet code that goes from the hottest stars down to the coolest ones: O, B, A, F, G, K, M. I know, it’s very counterintuitive. Long story short: it’s done this way due to historical reasons and we are just stuck with it. Astronomers then assign a numerical digit to these letters that runs from 0 (the hottest type of star within a given classification) to 9 (the coolest types). Alpha-2 is an A0 type star while the fainter component, Alpha-1 Canum Venaticorum, is an F0 type star.

Alpha-2 has a surface temperature of 11,450 Kelvin, is far more luminous than our Sun, being 113 times as bright and 3.0 times as massive. Alpha-1 on the other hand is much cooler at 6,785 Kelvin and is 5.6 times as bright as the Sun while containing only 1.5 solar masses.

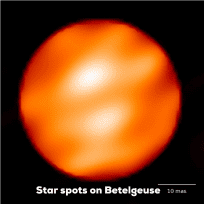

One of the more interesting things about Alpha-2 is that it belongs to a very curious category of variable stars known as a “spectrum variable”. Variable stars are stellar bodies that change in their luminosity, which is the total amount of energy they emit per unit of time. This is often due to the star being in an unstable part of their lives and they pulsate as they physically expand and contract. Sometimes this happen on such a scale and with such regularity that you and I can see this with the unaided eye or with some modest amount of optical assistance and many amateur astronomers monitor these kinds of stars in order to help the professional astronomers gain a more complete understanding of the lives of stars. Alpha-2 belongs to an unusual category of which it is the prototype. These so-called spectrum variables exhibit only very modest fluctuations in their energy output but show very marked fluctuations in their spectral lines. Astronomers can tease apart the continuous spectrum of light from a star right down to its individual dark and bright lines representing the absorption and emission of light at very specific wavelengths. The result is something that looks like a rainbow bar code and, just like a bar code, there is information hidden away in these spectral lines, information such as what kinds of chemical elements are present in the star’s atmosphere. Spectrum variable stars exhibit weird overabundances of elements such as silicon, mercury, and europium. It’s still not completely understood why this is, but it seems to be tied to the star’s very powerful magnetic field, which is some 5,000 times as powerful as the Earth’s. This powerful magnetic field generates massive “starspots” (just like our Sun’s famous sunspots) that always seem to be rotating in and out of view, creating the mild changes in luminosity. They may also be playing a role in the concentration of those chemical elements at the star’s surface.

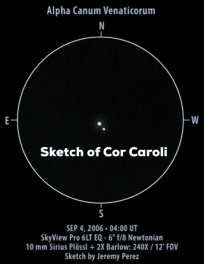

You won’t be able to visually detect the fluctuations in brightness in Cor Caroli, but you can see something else: color contrast. With a small telescope, you should see some very subtle differences in color between Alpha-1 and Alpha-2. The brighter primary star has a nice blueish tint while the fainter secondary appears more yellow. I always love sharing Cor Caroli with folks who are at my telescope during spring star parties. Hopefully, you might join me at one of these outings as we look up together in both awe and wonder.

For star party dates, times, and locations, just go to www.caasastro.org