Jungle Attacks

Gang conflict. Border patrols. Bloodshed in the jungle.

Recently you may have read about Dr. Sylvia Amsler of the UALR Department of Anthropology, and her involvement in the study of chimpanzees living in Uganda’s Kibale National Park.

Her work, which documented “lethal coalitionary attacks” between rival chimp groups made headlines in research circles, and around the world.

Out of general curiosity, and a desire for the UALR community to get first-person perspective from Sylvia, I sent her a few questions and she didn’t hesitate to respond. Below you’ll find a Q&A, in which Dr. Amsler graciously responds to an inappropriate initial question, and goes on to describe in detail not only her career path, but also the rigors and challenges of jungle research.

Q:Purely hypothetical. Let’s pretend someone is employed, for example, as a web designer, and would like to play with monkeys instead of being tied to his desk all day. Your web profile states that at one time, you were a primate keeper at the Little Rock Zoo. How does one obtain and/or apply for that job?

“Well, first I must correct the notion that zoo keepers get to “play with monkeys” – keepers work pretty hard cleaning and maintaining exhibits, preparing food, monitoring the health and well-being of the animals, and providing behavioral enrichment to them. It’s best for the primates if they have other primates of the same species to “play with” – so that they can live as natural a social life as possible.

That said, being a keeper is extremely rewarding, and therefore is a fairly coveted job. I feel quite lucky to have had the opportunity to get a job as a keeper at the Little Rock Zoo just when I needed and wanted one – during a 4 year tenure (my husband was in medical school here) in Little Rock between undergrad and grad school.

Spending time volunteering at the zoo, or in other animal care capacities, is a good way to make contacts and gain experience. In my case, I did a keeper internship at Brookfield Zoo in Chicago as an undergraduate. I then contacted keepers when I moved to Little Rock and volunteered for several months in both the great ape and carnivore departments before a position became available for which I could apply.

The fact that I had animal care experience and had made contacts here at the zoo undoubtedly helped me get my foot in the door. Having a degree in an animal-related field didn’t hurt either. So my advice to this hypothetical web designer would be to spend his/her off-time cheerfully chopping fruit and scooping poop in the extreme heat just for fun for as long as it takes for a position to open up. With the current economy though, it would be best to keep the day job.”

Q: Thank you for the career advice. Your time in Uganda, researching the chimpanzees – what was the most challenging aspect of that work? The most rewarding? Any other comments about that experience?

“The most challenging aspect is probably the physical demands of following chimpanzees. I leave camp at about 7am, and hike out until I find chimpanzees, which can take anywhere from 5 to 90 minutes. I then stay with the chimpanzees until 6pm before heading back to camp – again, a trek of anywhere from 5 to 90 minutes.

During this ~12 hour day, I spend a great deal of time scrambling to keep up with my subjects as they travel fairly quickly up and down the hilly terrain, sometimes on trails but more often through the forest and underbrush. Unlike the chimps, I carry a heavy backpack, hold an open notebook (in which I record observations during travel), and hold up my GPS unit to record their changing location.

At the end of the day I am generally exhausted, but need to stay up late enough to transfer all GPS points and handwritten data into my computer in case I lose my notebook (it happens!) At camp we use solar panels to charge car batteries during the day, providing a limited amount of electricity for lights and computers at night.

Pretty much everything else about field work is rewarding. I love living in the middle of the forest.

Our camp is situated on a hill overlooking a beautiful tropical rainforest. From this vantage point we are able to hear not only the calls of chimpanzees, but also multiple species of monkeys and birds, as well as occasional bellows of buffalo or elephants.

Being so close an observer of the lives of wild animals is truly an amazing experience. At Ngogo, my research site, hardly a day goes by that I don’t successfully contact chimpanzees. I follow these animals at a distance of about 5 meters and am sometimes completely surrounded by chimpanzees living their lives – feeding, grooming one another, resting, playing, and sometimes fighting.

One of the most dramatic events that I have been privileged to witness as a chimpanzee researcher is the topic of the paper that has just come out in Current Biology this week. Chimpanzees are a territorial species, and I focused on their territorial behavior in my dissertation research.

One of the most dramatic events that I have been privileged to witness as a chimpanzee researcher is the topic of the paper that has just come out in Current Biology this week. Chimpanzees are a territorial species, and I focused on their territorial behavior in my dissertation research.

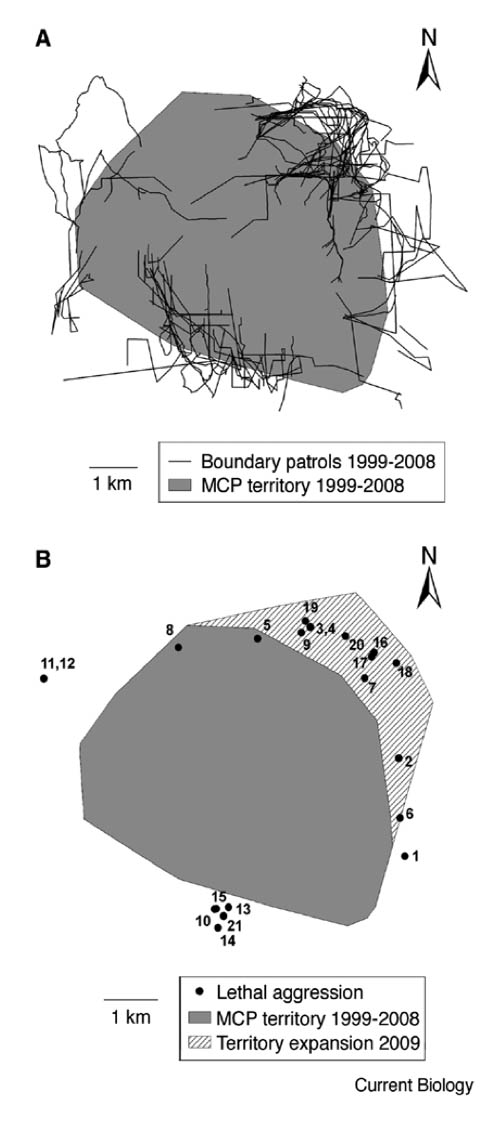

Large parties of males regularly patrol the boundaries of the community territory, sometimes leaving to make deep incursions into the territories of their neighbors. Their usual noisy, boisterous natures are quelled during these patrols, as they silently travel in a tight single-file formation. They pause regularly to listen for neighboring chimpanzees and to investigate any signs of chimpanzees that they encounter (such as feces, food trees, sleeping nests, etc.). They appear to be trying to make contact with other chimpanzees.

If the patrollers are able to find and isolate a single individual or very small party of chimpanzees from the other community, they will generally attack – with sometimes fatal consequences. Although it can be disturbing to watch chimpanzees killing other chimpanzees, it is also a fascinating behavior of our closest living relatives.

Data collected by myself and my colleagues, Dr. John Mitani from the University of Michigan and Dr. David Watts from Yale University, suggest that chimpanzees commit lethal aggression against stranger chimpanzees in order to gain territory. At Ngogo we have observed or inferred 21 instances of lethal aggression against neighbors over a 10-year period. 13 of these killings occurred in one particular area to the northeast of the Ngogo chimpanzees’ territory.

Last summer the Ngogo chimpanzees expanded their territory into the area formerly occupied by their northeastern neighbors, increasing territory size by about 20%. We have therefore provided the first direct evidence that territorial activities by chimpanzees, such as boundary patrols and lethal aggression, are adaptive because they can result in an increase in the feeding area available to all community members.”

(Dr. Sylvia Amsler is a lecturer in the UALR Department of Anthropology. To learn more about the program, visit ualr.edu/anthropology)