The Story of the Star Algol

We humans have a long history of populating the dark with all sorts of imaginary creatures. Whilst sitting around our ancient campfires, catching glimpses of vague shadows and hearing weird cries in the night, we let our imaginations run wild in an attempt to explain all those strange goings-on in the nocturnal world. It would take time and more level headed and braver souls to finally penetrate the darkness and figure out that, rather than ghosts and goblins frolicking in the dark, what we were actually seeing and hearing was nothing more than deer, rabbits, hedgehogs, and owls going about their nighttime activities.

We humans have a long history of populating the dark with all sorts of imaginary creatures. Whilst sitting around our ancient campfires, catching glimpses of vague shadows and hearing weird cries in the night, we let our imaginations run wild in an attempt to explain all those strange goings-on in the nocturnal world. It would take time and more level headed and braver souls to finally penetrate the darkness and figure out that, rather than ghosts and goblins frolicking in the dark, what we were actually seeing and hearing was nothing more than deer, rabbits, hedgehogs, and owls going about their nighttime activities.

These bold adventurers were our first scientists; their curiosity compelled them to explore their world for answers and to not take unfounded explanations at face value. But it wasn’t just strange sights and sounds in the dark to which our ancestors would ascribe supernatural explanations; we did the same in order to explain all those bright lights in our day and nighttime sky as well. To properly explain them would require more sophisticated observations and technologies than was available to our ancient ancestors.

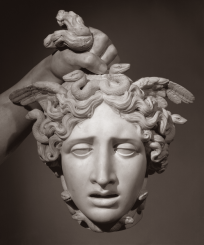

Allow me to draw your gaze to a star in our northern sky that has long had a rather sinister reputation. The star’s name is Algol and it can be found within the constellation of Perseus. If you know your Greek mythology you will recall that Perseus is the young man who slew Medusa, the hideous woman with snakes for hair and whose glance could turn people to stone. To honor Perseus’ bravery the gods immortalized him as a constellation in our northern sky.

Allow me to draw your gaze to a star in our northern sky that has long had a rather sinister reputation. The star’s name is Algol and it can be found within the constellation of Perseus. If you know your Greek mythology you will recall that Perseus is the young man who slew Medusa, the hideous woman with snakes for hair and whose glance could turn people to stone. To honor Perseus’ bravery the gods immortalized him as a constellation in our northern sky.

Perseus can be found at this time of the year by facing towards the northeast at nightfall and looking first for the constellation of Cassiopeia, whose five bright stars resemble the letter W standing on its side. Using the central star of Cassiopeia, Gamma Cassiopeiae, draw out an imaginary line from it and straight through the bright star below it, Ruchbah, and extend that line for about three times the distance between these two to arrive at Perseus.

Perseus can be found at this time of the year by facing towards the northeast at nightfall and looking first for the constellation of Cassiopeia, whose five bright stars resemble the letter W standing on its side. Using the central star of Cassiopeia, Gamma Cassiopeiae, draw out an imaginary line from it and straight through the bright star below it, Ruchbah, and extend that line for about three times the distance between these two to arrive at Perseus.

Now that we have found Perseus we have to locate Algol. To do that just look for the brightest star in Perseus, Mirfak, which shines about as brightly to our eyes as do the stars that make up the Big Dipper. About five degrees (five degrees is the width of your fist held out at arm’s length) to the right (east) and a little southward’s from Mirfak and you will come to the slightly dimmer star Algol.

At first glance Algol doesn’t look all that special, but if you watch it over time you will see that there is something rather peculiar going on here: Algol blinks! Well, sort of. It’s a rather long, drawn out blink. Hold that thought; I’m coming back to it in just a moment.

Here’s the deal though… Algol happens to be the star that marks the location of Medusa’s severed head being held by Perseus. DUN-DUN-DUUUUN!

Creepy, eh? But that’s not all. The name Algol comes from the Arabic “Ra’s-al-Ghul”, which means “The Demon’s Head” (Batman fans will also immediately recognize “Ra’s-al-Ghul” as the name of one of the cowled one’s arch enemies). Arabic cultures were not the only ones to see something sinister with Algol. To the Chinese the star is known as Tseih She, which translates as “the piled-up corpses”. Sheesh, what the heck is up with Algol to have gotten such a sinister reputation? Well, as far as these ancient cultures go, we just don’t know; they left no written record as to why this star was giving them the heebie jeebies. Maybe they noticed the star’s blinking nature, or maybe not, but without any kind of evidence we can only speculate.

The first recorded observations of Algol’s blinking comes to us via 17th century Italian astronomers. But is was a 19 year old, 18th century, English astronomer named John Goodricke who not only worked out the schedule of Algol’s blinking but also put forth the correct hypothesis as to why.

astronomer named John Goodricke who not only worked out the schedule of Algol’s blinking but also put forth the correct hypothesis as to why.

Now, I keep saying that Algol blinks but it is more correct to say that it’s brightness varies noticeably over time: Algol is a “variable star”. Why should a star’s brightness fluctuate? Broadly speaking there are two reasons why some stars exhibit this behavior. The first is due to something intrinsic with it. In other words there is something physically going on with the star. In many cases this involves the star periodically swelling and shrinking in size while in others it may involve the star temporarily flaring up in brightness. Then we have stars that vary in brightness due to some kind of extrinsic factor. This is often due to a binary companion that happens to lie along our line of sight and occasionally eclipses its partner while dimming some of its light.

By diligently monitoring Algol young Mr. Goodricke calculated the period between the star’s maximum and minimum brightness as being 2 days, 20 hours, 48 minutes and 56 seconds (actually he was a little off from this with his calculations but he was very, very close nonetheless). Goodricke reckoned (correctly) that Algol is not one star, but two. He figured that there must be one bright star and one dimmer one orbiting around each other very closely and that every two and a half days the fainter one would pass in front of the brighter one, producing Algol’s distinctive, slow blink. Sadly, Goodricke’s very promising career in astronomy was cut short by his untimely death at the age of 21 in 1786.

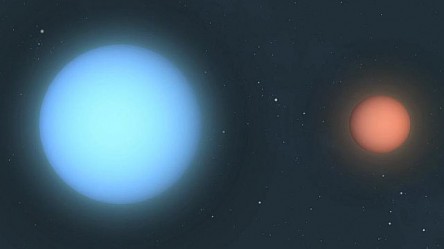

Today we know that Algol is the closest eclipsing binary star system to Earth at a distance of around 94 light years. The bright primary star is a blue-white B-type star (B-type stars are very massive, very luminous, and very, very hot) and the companion is a less massive, cooler, and dimmer orange K-type giant star. The sequence of the stellar classification system, running from hottest to coolest is O, B, A, F, G, K, and M. and astronomy students are well familiar with the pneumonic “Oh Be A Fine Gal/Guy Kiss Me” to help them remember it come exam time.

You too can duplicate Goodricke’s observations with nothing more than a pair of binoculars and a keen eye. By carefully monitoring Algol you will see it pass from it’s normal apparent magnitude of 2.1 to 3.4 and back again to 2.1 (the apparent magnitude scale is calibrated in such a way that for every difference of 1 magnitude the star’s brightness will change by a factor of 2.5 times). It’s a good idea to start out by using some comparison stars whose apparent magnitudes are fixed and not variable. For example, nearby Mirfak shines at a magnitude of 1.8 while Zeta Persei is at 2.9. You can also make use of Algol minima schedules in magazines like Sky & Telescope, Astronomy Magazine, or web sites like this one: http://rfo.org/jackscalendar.html.

Once you’ve got a handle on Algol’s magnitude you can begin monitoring its change in brightness. You will see that the biggest drop in Algol’s magnitude occurs when the dimmer companion star eclipses the primary, thus blocking out a considerable portion of its light. From beginning to end the eclipse lasts for about ten hours and Algol is at its minimum for about two hours. Much fainter, and not detectable to the eye, is a second drop in brightness as the primary star eclipses the secondary. Of course you won’t actually see the stars physically eclipsing one another because they are too close together.

If you want to be a really good observer and would like a fun little project to do you can plot a light curve for Algol.  A light curve is nothing more than a graph that plots out the star’s change in magnitude over time. Many amateur astronomers specialize in variable star observing, so much so that there is even an organization devoted to it called, oddly enough, the American Association of Variable Star Observers. On their website you can learn how to make observations and even generate some light curve charts: http://www.aavso.org/lcg. This is where the hobby of amateur astronomy can actually make real contributions to the science of astronomy. The data collected by the hobbyists can then be used by the professionals in order to better understand a range of topics related to stellar life histories.

A light curve is nothing more than a graph that plots out the star’s change in magnitude over time. Many amateur astronomers specialize in variable star observing, so much so that there is even an organization devoted to it called, oddly enough, the American Association of Variable Star Observers. On their website you can learn how to make observations and even generate some light curve charts: http://www.aavso.org/lcg. This is where the hobby of amateur astronomy can actually make real contributions to the science of astronomy. The data collected by the hobbyists can then be used by the professionals in order to better understand a range of topics related to stellar life histories.

We’ve come a long ways since those ancient times of being afraid of the dark. Today we have new knowledge and new technologies that allow us to slowly chip away at the mysteries of how the universe works. And even those of us who are non-scientists are able to pick up a torch and penetrate the darkness.