Looking up at a star-filled sky, it becomes a tempting thought to try and start connecting all of those dots in order to make your own set of constellations. We humans have been doing just that for thousands, if not millions, of years. Our brains are hardwired to impose order upon chaos and to seek out familiar patterns and shapes where none really exist. The psychological term for this is “pareidolia” and it is this tendency to find patterns amongst random “noise” (combined with our inherent need to tell each other stories) that we have constellations in the first place.

Ever since the 1930’s, professional astronomers, have officially recognized 88 different constellations. Each constellation has its own clearly defined borders and are used to both divide the northern and southern hemisphere skies into manageable sections and for mapping out the stars and various other objects in the night sky. In astronomy the naming of constellations, stars, planets, and all other celestial objects is handled by the International Astronomical Union, their word is law and is recognized by all professional astronomers the world over. In short, if you had thoughts of creating your own constellation and naming it after David Bowie or your Aunt Millie then you should just forget about it, the IAU has already set in stone the constellations and there won’t be new ones created anytime soon.

Amateur astronomers recognize the authority of the IAU too but aren’t quite as beholden to them as are their professional counterparts. Here’s the deal, many of those clearly defined constellations created by the IAU are not so easy to see by the casual backyard stargazer. The amateur astronomer wants to find celestial objects easily and quickly and for most of the history of the hobby, things like computerized go-to telescopes were simply not around. So, in order to find constellations and celestial objects, amateur astronomers often use unofficial star patterns they have created on their own, often using the brightest stars from one or more of the officially recognized constellations. These unofficial star patterns are known as “asterisms”. You are probably familiar with a few already. The Big and Little Dippers in the constellations of Ursa Major and Ursa Minor respectively, are two good examples. Others include the Belt of Orion in the constellation of Orion and the Northern Cross in the constellation of Cygnus the Swan. One of the biggest and brightest of asterism is easily seen in our night sky right now. It goes by various names, but I prefer to call it the Winter Hexagon

WHEN AND WHERE TO LOOK

At around 9:00 P.M. on these February nights, go outside and face south. Locate Sirius, the brightest star in our night sky. Sirius marks the bottom, pointy end of the hexagon. Now, using the chart I have included here, we are going to move in a clockwise fashion to trace out the hexagon using 6 more bright stars. Procyon is our next stop, followed by Pollux and Castor. The bright star Capella is practically overhead and marks the top pointy end of the hexagon. Moving on to the western side of this geometric shape, we will find the star Aldebaran, Rigel, and then back to Sirius to complete the hexagon pattern.

At around 9:00 P.M. on these February nights, go outside and face south. Locate Sirius, the brightest star in our night sky. Sirius marks the bottom, pointy end of the hexagon. Now, using the chart I have included here, we are going to move in a clockwise fashion to trace out the hexagon using 6 more bright stars. Procyon is our next stop, followed by Pollux and Castor. The bright star Capella is practically overhead and marks the top pointy end of the hexagon. Moving on to the western side of this geometric shape, we will find the star Aldebaran, Rigel, and then back to Sirius to complete the hexagon pattern.

WHAT YOU ARE SEEING

Sir Patrick Moore

The Winter Hexagon, also known as the Winter Circle or the Winter Football, is nothing more than an asterism, an unofficial star pattern made up of seven bright stars found within six different officially designated constellations. While it lacks any kind of official status from the International Astronomical Union, it is a useful device for identifying a number of different stars and constellations in our winter sky.

H.A. Rey

While I’m not sure who first came up with this star pattern it was made popular in the 1950’s by H.A. Rey (creator of Curious George) author of “The Stars: A New Way To See Them” (an indispensable book in the library of the beginning stargazer ages 9 to 99) and the British amateur astronomer Sir Patrick Moore, host of the long running TV series, The Sky At Night.

One of the first things that you will notice when stargazing in winter is that the stars seem so much brighter at this time of year compared to the stars of summer. The reason for this is that, during the summer, you are looking towards the central portions of our Galaxy, across some 75,000 light years of space jam-packed with both stars and lots of obscuring dust, thus muting the brightness of individual stars. In winter however, our view changes, and we are looking more along the length of the spiral arm within which our own Sun resides. In this direction, there happens to be a number of fairly large, bright, and relatively nearby stars compared to the views afforded us in summer. This view towards the “suburbs” of our Galaxy compared to the dusty, “inner city” views of the Galaxy in the summer is why the winter stars look so much brighter.

Let’s take a closer look at the individual stars that make up the Winter Hexagon.

Canis Major

Blue-white Sirius, the “dog star”, in addition to being the brightest star in the constellation of Canis Major, the Great Dog, also happens to be the brightest star in our night sky, shining at a magnitude of -1.46. It is also fairly close to Earth at a distance of about 8.6 light years. Sirius is actually a double star system with a white dwarf companion (Sirius B). A white dwarf is the small, ultra-dense, dead cores of Sun-like stars. The Ancient Greek astronomers knew that during the summer months Sirius was located very close to the Sun upon the sky. They thought that the combined heat of Sirius and the Sun is what made July and August so miserably hot. This is where we get the phrase “dog days of summer”.

Sirius companion

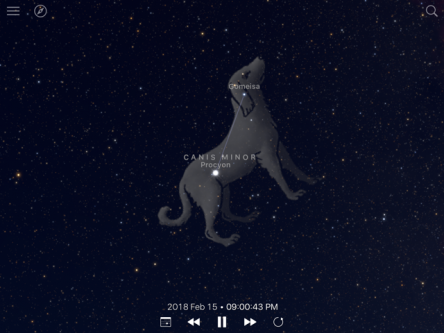

Canis Minor

Sirius appears blue-white, but Procyon looks decidedly white to the naked eye. Use a pair of binoculars however and you may see that the star has a more cream-colored appearance. Procyon is the alpha star within the constellation of Canis Minor, the Little Dog. It’s not quite as bright as Sirius however, with an apparent magnitude of 0.34. The name “Procyon” means “preceding the dog” and refers to the fact that the star and the constellation rise a little bit before both Sirius and the constellation of Canis Major. Like Sirius, Procyon has a white dwarf companion and the star system is relatively close to Earth at some 11.45 light years away.

Pollux and Castor are the two brightest stars in Gemini, the Twins. In fact, the stars mark the heads of the twins and the star names are also the names of the mythological brothers. The brightest of the two is Pollux, it is a giant orange star located some 35 light years away. It is nearly 10 times the size of our Sun and some 40 times brighter. In our sky, it has an apparent magnitude of 1.16. Look at through binoculars to see its orange-yellow tint.

Pollux and Castor are the two brightest stars in Gemini, the Twins. In fact, the stars mark the heads of the twins and the star names are also the names of the mythological brothers. The brightest of the two is Pollux, it is a giant orange star located some 35 light years away. It is nearly 10 times the size of our Sun and some 40 times brighter. In our sky, it has an apparent magnitude of 1.16. Look at through binoculars to see its orange-yellow tint.

Our next stop is Capella, sixth brightest star in our night sky shining with an apparent magnitude of 0.08 and the brightest star in the constellation of Auriga, the charioteer.  Yellow-white Capella has a surface temperature very much like that of our own Sun and is located at a distance of 43 light years. While it looks like just one star, Capella is in fact a four-star system composed of two binary pairs. According to myth, the charioteer is Ericthonius, the crippled son of Vulcan and Minerva. He is said to have invented the chariot. He is also said to have had a soft spot for animals and he is often illustrated holding three goats. Capella is said to be Amalthea, a she-goat who once suckled the infant Zeus.

Yellow-white Capella has a surface temperature very much like that of our own Sun and is located at a distance of 43 light years. While it looks like just one star, Capella is in fact a four-star system composed of two binary pairs. According to myth, the charioteer is Ericthonius, the crippled son of Vulcan and Minerva. He is said to have invented the chariot. He is also said to have had a soft spot for animals and he is often illustrated holding three goats. Capella is said to be Amalthea, a she-goat who once suckled the infant Zeus.

Aldebaran is an orange giant star, nearing the end of its life, and marking the southern eye of Taurus the bull. Like most geriatric stars of its type, Aldebaran has nearly depleted its fuel supply within its core. The core has shrunk, gotten really hot, and has caused the outer layers of the star to swell. This makes the star appear very big and very luminous. Aldebaran has a diameter 40 times that of the Sun and is 400 times brighter. Just a few degrees to the west of Aldebaran is the famous Pleiades, or Seven Sisters, star cluster. If you watch closely, you will see that Aldebaran and the Pleiades (as do all the other stars in this part of the sky) move from east to west hour by hour. In fact, the name “Aldebaran” comes from the Arabic “al-dabaran”, meaning, “the follower”. This alludes to the fact that Aldebaran seems to be following the Pleiades across the sky. The fiery red eye of the bull is located some 65 light years from Earth.

Aldebaran is an orange giant star, nearing the end of its life, and marking the southern eye of Taurus the bull. Like most geriatric stars of its type, Aldebaran has nearly depleted its fuel supply within its core. The core has shrunk, gotten really hot, and has caused the outer layers of the star to swell. This makes the star appear very big and very luminous. Aldebaran has a diameter 40 times that of the Sun and is 400 times brighter. Just a few degrees to the west of Aldebaran is the famous Pleiades, or Seven Sisters, star cluster. If you watch closely, you will see that Aldebaran and the Pleiades (as do all the other stars in this part of the sky) move from east to west hour by hour. In fact, the name “Aldebaran” comes from the Arabic “al-dabaran”, meaning, “the follower”. This alludes to the fact that Aldebaran seems to be following the Pleiades across the sky. The fiery red eye of the bull is located some 65 light years from Earth.

Our final stop is Rigel, the brightest star in the constellation of Orion the hunter and marks his left foot. Rigel is a monster star, a blue-white supergiant that is 70 times bigger than the Sun and over 50,000 times brighter. It is also much hotter than the Sun with a surface temperature of about 20,000 degrees Fahrenheit, the Sun has a surface temperature of about 10,000 degrees F. Giant Rigel is located some 850 light years away, the light hitting your eye tonight when you look at it, left the star in about the year 1168, the year Prince Richard of England became Duke of Aquitaine, later he would become King Richard I of England. If you remember your mythology, you will recall that Orion met his end by being stung on the heel by a scorpion (seen in our summer sky as the constellation of Scorpius), Rigel marks the spot where he was stung.

Our final stop is Rigel, the brightest star in the constellation of Orion the hunter and marks his left foot. Rigel is a monster star, a blue-white supergiant that is 70 times bigger than the Sun and over 50,000 times brighter. It is also much hotter than the Sun with a surface temperature of about 20,000 degrees Fahrenheit, the Sun has a surface temperature of about 10,000 degrees F. Giant Rigel is located some 850 light years away, the light hitting your eye tonight when you look at it, left the star in about the year 1168, the year Prince Richard of England became Duke of Aquitaine, later he would become King Richard I of England. If you remember your mythology, you will recall that Orion met his end by being stung on the heel by a scorpion (seen in our summer sky as the constellation of Scorpius), Rigel marks the spot where he was stung.

Get outside and become acquainted with the Winter Hexagon and the fascinating stars and constellations that comprise it. I think that you will find the Hexagon a useful way to begin your explorations of our night sky.