Imagine yourself in a spaceship, far “above” the solar system. Looking “down” from your ship’s viewport, you would see the Sun and its eight planets orbiting around it, all, more or less, within the same level plane. From the surface of the Earth, we too can see this orbital plane of the planets around the Sun. It’s the highway across the sky through which the Sun, moon, and the visible planets all appear to travel over the course of a year. By tracing out this highway in the sky, it would appear as a curved line that stretches from the eastern to the western horizon.

In ancient times, sky watchers called this highway in the sky the “ecliptic”, for it was along this stretch of sky that solar or lunar eclipses occurred. The ecliptic is also where you find the constellations of the zodiac. As the Earth spins upon its axis, the Sun appears to move through these 12 (actually 13 since the Sun also moves through the constellation of Ophiuchus) constellations and, since humans have always looked to the sky to divine meaning here on Earth, they became important star patterns to early astrologers.

As the planets orbit around the Sun they do so at different speeds, the fastest of course are the inner planets, Mercury and Venus, while the outer visible planets, Jupiter and Saturn, are relative slow pokes. Since all the planets are orbiting within the same plane at different speeds, there are times when, viewed from here on Earth, they appear to line up close to one another in the sky. These close groupings are called “planetary conjunctions” and they can be quite lovely things to observe with just your unaided eye.  Sometimes the moon even gets in on the act and you might see one or two bright planets snuggled up next to the moon in the evening or dawn sky. The angular separations in a conjunction can be less than one degree apart (one degree is equivalent to the width of your pinkie finger held out at arm’s length) to as much as five degrees of separation (a fist width held out at arm’s length). Not every planetary conjunction is aesthetically pleasing, or obvious, especially when a bright planet happens to align with a fainter, more distant world. However, these kinds of conjunctions are special in their own right since they can help planet watchers easily locate otherwise hard to see worlds. While conjunctions of one sort or another are not at all uncommon there are two this month that I want to draw your attention to: one is of the more visually appealing variety and can be appreciated without optical aid while the other involves the pairing of a bright and a dim planet; optical aid will be required but the payoff is worth the effort.

Sometimes the moon even gets in on the act and you might see one or two bright planets snuggled up next to the moon in the evening or dawn sky. The angular separations in a conjunction can be less than one degree apart (one degree is equivalent to the width of your pinkie finger held out at arm’s length) to as much as five degrees of separation (a fist width held out at arm’s length). Not every planetary conjunction is aesthetically pleasing, or obvious, especially when a bright planet happens to align with a fainter, more distant world. However, these kinds of conjunctions are special in their own right since they can help planet watchers easily locate otherwise hard to see worlds. While conjunctions of one sort or another are not at all uncommon there are two this month that I want to draw your attention to: one is of the more visually appealing variety and can be appreciated without optical aid while the other involves the pairing of a bright and a dim planet; optical aid will be required but the payoff is worth the effort.

MARS MEETS URANUS

Okay, a show of hands: how many of you have ever seen Uranus? Oh stop! I doubt that very many of you have ever gazed upon the seventh planet. It’s just so far away from us, being, on average, about 1.784 billion miles from the Sun, that it is not readily visible to us with the unaided eye. That being said, if you have exceptionally dark skies and very good eyesight,  you might be one of those folks who can pick it out from amongst the background stars without the need of any optical aid. But this month, you can use the bright planet Mars to find Uranus, and you can even get both worlds within the same binocular field of view.

you might be one of those folks who can pick it out from amongst the background stars without the need of any optical aid. But this month, you can use the bright planet Mars to find Uranus, and you can even get both worlds within the same binocular field of view.

On the night of February 12th, Mars will lie just a little over one degree to the NW of Uranus. But there will be a slight problem for those who might want to try their hand at finding Uranus with the unaided eye: the moon. The moon will be at first quarter this evening and its glare could prove problematic, possibly even for binocular users. The good news is that you can get the two planets in the same binocular FOV around a week centered on that date.

If you are in doubt, try and observe on the night of February 8th, when the moon is just a crescent. On that evening, the two planets are almost two degrees apart, with Mars just to the southwest of Uranus. On the night of February 13th, the planets stand 1.1 degrees apart, with Uranus now due south of Mars.

While these two worlds appear very close together upon the sky that is not the case, as with any other conjunction, this is just a line of sight effect from our perspective here on Earth. In reality, the two are very far apart from one another out in space. On the night of February 12th, Mars is over 150 million miles away from Earth, while Uranus is around 1.86 billion miles distant. These vast distances are reflected in both their visual magnitudes as well as their angular size when viewed through a telescope. Mars, being the closer of the two planets, is shining at magnitude 1, while Uranus, the more distant planet, is at magnitude 5.8 (magnitude 6 is generally considered the cut off limit for naked eye visibility), making Mars some 250 times brighter than Uranus. Last summer, when Mars was very close to Earth, it had an angular size of 24.3 arc seconds, now, as it has moved further and further away, is has shrunk down to a mere 5.7 arc seconds across (so don’t expect to see surface features on Mars if you are using a telescope). Uranus is even smaller at 3.5 arc seconds in size.

Being so small, you might be wondering how to be able to pick out the planet Uranus from amongst the background stars. Well, with optical aid, the planet will appear as a blue-green dot. Why so blue?  Uranus is composed of hydrogen, helium, water, ammonia, and methane. When sunlight hits the upper atmosphere of the planet, the methane absorbs the redder portions of the light while reflecting the blue-green portions back to our eyes. You might have a hard time resolving the pair as discs in binoculars or a small telescope at low magnifications, but you should have no problem at all in being able to see the color contrasts between the two.

Uranus is composed of hydrogen, helium, water, ammonia, and methane. When sunlight hits the upper atmosphere of the planet, the methane absorbs the redder portions of the light while reflecting the blue-green portions back to our eyes. You might have a hard time resolving the pair as discs in binoculars or a small telescope at low magnifications, but you should have no problem at all in being able to see the color contrasts between the two.

THE MOON MEETS JUPITER

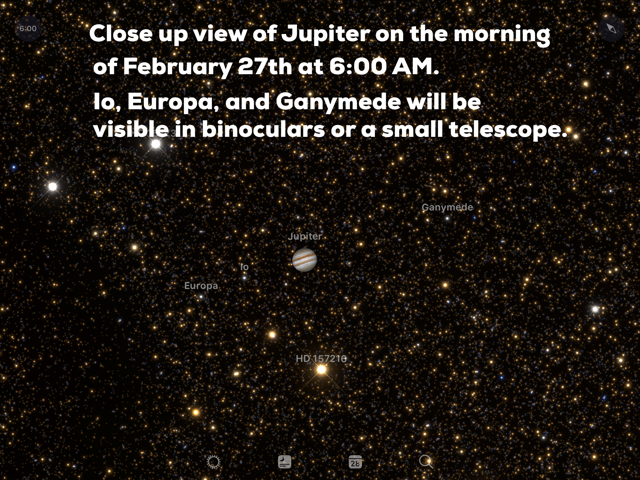

Closing out the month, during the predawn hours of February 27th, the waning moon and the planet Jupiter will form a dramatic pairing. Grab a cup of your favorite hot beverage, bundle up, stumble outside and face south before sunrise. There you will see a gorgeous crescent moon less than 2 degrees to the north of the fifth planet in our solar system, Jupiter. Jupiter is headed towards becoming an object in our evening sky but right now you can see it during the dawn hours. As Jupiter and Earth get closer to one another in their respective orbits, the King of the Planets is growing in angular size this month from 34 arc seconds across to 36 seconds of arc. With a pair of binoculars, you might see some, or all, of its four largest moons: Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto. With a small telescope, you can see the major features of the giant planet’s cloud tops: the dark belts and bright zones.

Closing out the month, during the predawn hours of February 27th, the waning moon and the planet Jupiter will form a dramatic pairing. Grab a cup of your favorite hot beverage, bundle up, stumble outside and face south before sunrise. There you will see a gorgeous crescent moon less than 2 degrees to the north of the fifth planet in our solar system, Jupiter. Jupiter is headed towards becoming an object in our evening sky but right now you can see it during the dawn hours. As Jupiter and Earth get closer to one another in their respective orbits, the King of the Planets is growing in angular size this month from 34 arc seconds across to 36 seconds of arc. With a pair of binoculars, you might see some, or all, of its four largest moons: Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto. With a small telescope, you can see the major features of the giant planet’s cloud tops: the dark belts and bright zones.

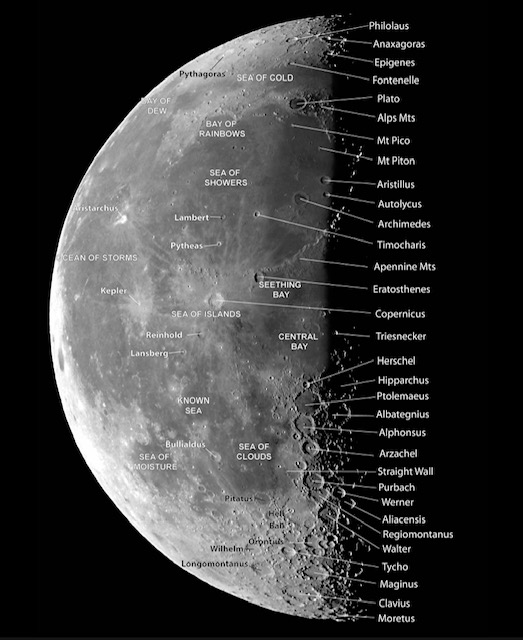

With binoculars, you can see some of the moon’s maria (“seas”), such as the Sea of Showers and Bay of Rainbows in the north, the Ocean of Storms on the western limb and the Sea of Clouds to the south. A small telescope will reveal spectacular views of craters in sharp relief along the terminator, the line the divides the day from the night side. Look for large rayed craters such as Copernicus and Kepler, the rays having been formed from ejecta that resulted from large meteor impacts.

There is nothing like a good conjunction to catch the eye and make us aware of the amazing sights our night sky can offer. Sometimes they are dramatic and startling to behold, other times they are more subtle but still capable of revealing great wonder and beauty if we just take the time to look.