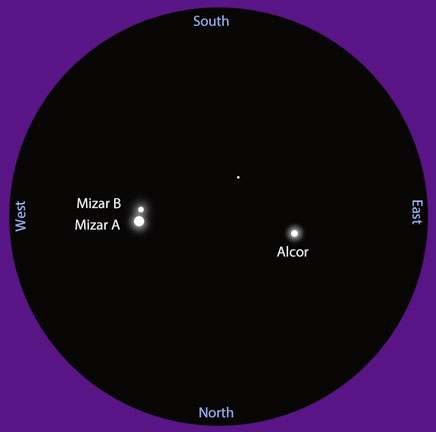

Many amateur astronomers take particular joy in observing and showing off double stars in their telescopes. There is just something delightful about looking at a star that, to the naked eye, advertises itself as one but, upon closer inspection, turns out to be two, or even more, individual stars. A classic example is the star Mizar, in the handle of the Big Dipper. Even with the unaided eye you can usually see a very faint companion, Alcor, hugging closely to the brighter Mizar. With even a modest amount of aperture, a small telescope reveals a third star associating with the first two as well as another faint companion to Mizar. Wonderful!

Many amateur astronomers take particular joy in observing and showing off double stars in their telescopes. There is just something delightful about looking at a star that, to the naked eye, advertises itself as one but, upon closer inspection, turns out to be two, or even more, individual stars. A classic example is the star Mizar, in the handle of the Big Dipper. Even with the unaided eye you can usually see a very faint companion, Alcor, hugging closely to the brighter Mizar. With even a modest amount of aperture, a small telescope reveals a third star associating with the first two as well as another faint companion to Mizar. Wonderful!

The great thing about many of these double and multiple stars is that they can be seen with binoculars or a small telescope under just about any kind of sky condition, no matter your level of experience. Now, these “double stars” come in two basic flavors: those that are purely optical, a line of sight effect and have no physical relationship to one another, and those that are indeed gravitationally bound to one another. Let’s go back to Mizar and Alcor. These two main components are separated from one another by about 3-light years, so they are not true binaries. However, it turns out that Mizar A and B are both binary stars (you can’t see these components in a telescope, their presence is only revealed by the use of spectroscopy), making Mizar a true quadruple star system!

This month, I want to direct your attention to a multiple star group whose components are all physically related, Sigma Orionis, in the constellation of Orion the Hunter. Let’s go!

HOW TO FIND IT

Easy peasy. All you need to do is locate the star Alnitak, the most southeastern star in the Belt of Orion. Next, look just one degree below (one degree is the width of your pinkie finger held out at arm’s length) and to the southwest of Alnitak. Through your finder scope, Sigma Orionis will appear as a moderately dim star.

Unfortunately, Sigma Orionis will not reveal its splendor through binoculars, you will need at least a small telescope to see it at its best. Lower power magnifications will show them at their finest.

WHAT YOU ARE SEEING

Sigma Orionis is in fact a 5-star system, but you are likely only going to be able to see four components. The brightest is Sigma A, its B component is so close to it, being about 90 Astronomical Units (AU) apart (that comes out to about 9.3 billion miles, very far apart by earthly standards, but practically rubbing shoulders on astronomical scales) that a backyard telescope will not split them. These two stars are massive, hot, blue giants and orbit around one another once every 170 years.

Sigma Orionis is in fact a 5-star system, but you are likely only going to be able to see four components. The brightest is Sigma A, its B component is so close to it, being about 90 Astronomical Units (AU) apart (that comes out to about 9.3 billion miles, very far apart by earthly standards, but practically rubbing shoulders on astronomical scales) that a backyard telescope will not split them. These two stars are massive, hot, blue giants and orbit around one another once every 170 years.

Strung out in an irregular line from Sigma A/B are the other three components, C, D, and E. D, the faintest of the three, lies some 4,600 AU away from A/B (over 400 billion miles) while C is 3,900 AU distant from the pair and E is a whopping 15,000 AU away (over 2 trillion miles!).

One day, C, D, and E will lose their gravitational bond with A/B and will drift away as lone stars, just like our own Sun. A/B and E, being massive blue stars, will one day end their lives in a supernova, while the C and D components will likely finish off their lives as white dwarfs, the hot exposed cores of middling mass stars like the Sun. The fierce radiation from Sigma Orionis A/B is partially responsible for exciting the gas and dust surrounding the famous Horsehead Nebula.

Pay attention and see if you can detect any color associated with Sigma Orionis. Many people report seeing colors such as red, orange, yellow, grape, and pale gray with this grouping. I have trouble seeing it myself, but if you do, let me know!

Pay attention and see if you can detect any color associated with Sigma Orionis. Many people report seeing colors such as red, orange, yellow, grape, and pale gray with this grouping. I have trouble seeing it myself, but if you do, let me know!

As an added bonus, look just to the northwest of Sigma Orionis to see the lovely three-star system, Struve 761.

Far from being mere pinpoints of light in the sky, the stars can offer you a multitude of observational pleasure, all you need do is get out and look up, in both awe and wonder.