There is a common misconception that astronomers do nothing but sit at a telescope every night enjoying celestial eye candy. In fact, for newbies in amateur astronomy, that seems to be the primary motivation for wanting to buy a telescope: the expectation that their images at the eyepiece will be comparable to what they have seen as colorful photographs in magazines or online. The sad truth is that the human eye is just not that sensitive. The astronomical photographs that you see in the pages of glossy magazines were made by long exposure photography using cameras with very sensitive light detecting sensors and then processed with specialized astrophotography computer software.

There is a common misconception that astronomers do nothing but sit at a telescope every night enjoying celestial eye candy. In fact, for newbies in amateur astronomy, that seems to be the primary motivation for wanting to buy a telescope: the expectation that their images at the eyepiece will be comparable to what they have seen as colorful photographs in magazines or online. The sad truth is that the human eye is just not that sensitive. The astronomical photographs that you see in the pages of glossy magazines were made by long exposure photography using cameras with very sensitive light detecting sensors and then processed with specialized astrophotography computer software.

Still, that does not mean that there aren’t any beautiful things to see in the heavens and this month we are going to step outside in order to enjoy one such vision of loveliness. Best of all, you don’t even need a telescope to see it, just an ordinary pair of binoculars will do.

WHAT ARE WE LOOKING FOR?

The human eye and brain, in all of their staggering complexity, are the products of millions of years of biological evolution and, working in tandem, they are remarkably good at picking out patterns from otherwise random noise. In the outer layer of the human brain is a system of neural networks that facilitates the processing of visual and auditory patterns, which enhances our ability to match information from a given stimulus with information that we have stored away as memory. Facial recognition, being able to find and consume edible plants and to distinguish them from plants that are toxic, as well as remembering locations are all abilities that have enhanced our chances of survival as a species and they are all made possible by our built-in pattern recognition software. But beyond our ability to discern between hazards and useful resources, our brains are also prone to seeing patterns where none really exist. Ever seen a bunny rabbit in the clouds? Elvis’s face in a potato? If so, then you know what I’m talking about. This type of pattern recognition is called “pareidolia” and, to a certain extent, it can be used to explain how and why our ancient ancestors saw patterns among the stars, bequeathing to us our modern-day constellations.

The human eye and brain, in all of their staggering complexity, are the products of millions of years of biological evolution and, working in tandem, they are remarkably good at picking out patterns from otherwise random noise. In the outer layer of the human brain is a system of neural networks that facilitates the processing of visual and auditory patterns, which enhances our ability to match information from a given stimulus with information that we have stored away as memory. Facial recognition, being able to find and consume edible plants and to distinguish them from plants that are toxic, as well as remembering locations are all abilities that have enhanced our chances of survival as a species and they are all made possible by our built-in pattern recognition software. But beyond our ability to discern between hazards and useful resources, our brains are also prone to seeing patterns where none really exist. Ever seen a bunny rabbit in the clouds? Elvis’s face in a potato? If so, then you know what I’m talking about. This type of pattern recognition is called “pareidolia” and, to a certain extent, it can be used to explain how and why our ancient ancestors saw patterns among the stars, bequeathing to us our modern-day constellations.

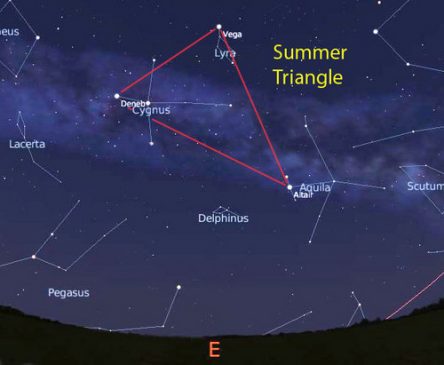

While our pareidolia-induced star patterns have all been officially established by the International Astronomical Union since 1930, people are still determined to see patterns among the stars and, sometimes, these shapes and patterns become widely used by amateur astronomers to help the navigate their way around the night sky , despite their not being officially recognized by the IAU. We call these unofficial star patterns, “asterisms”. The Big Dipper and the Summer Triangle are two such well known asterisms.

While our pareidolia-induced star patterns have all been officially established by the International Astronomical Union since 1930, people are still determined to see patterns among the stars and, sometimes, these shapes and patterns become widely used by amateur astronomers to help the navigate their way around the night sky , despite their not being officially recognized by the IAU. We call these unofficial star patterns, “asterisms”. The Big Dipper and the Summer Triangle are two such well known asterisms.

One night in 1980, Father Lucian Kemble, a Franciscan priest and avid astronomer, was outside his home in Alberta, Canada, exploring the sky with his trusty 7×35 pair of binoculars. As he swept them across the southwestern corner of the rather obscure constellation of Camelopardalis, the giraffe, he noticed something that caused him to do a double take: “a beautiful cascade of faint stars tumbling from the northeast down to the open cluster NGC 1502.” Finding no reference to this striking chain of stars, the good Father realized that he had discovered something that no one had ever noticed before, and all with his simple, inexpensive 7×35 binoculars. He immediately dashed off a letter announcing his find to Walter Scott Houston, Deep-Sky Wonders columnist for Sky & Telescope.

One night in 1980, Father Lucian Kemble, a Franciscan priest and avid astronomer, was outside his home in Alberta, Canada, exploring the sky with his trusty 7×35 pair of binoculars. As he swept them across the southwestern corner of the rather obscure constellation of Camelopardalis, the giraffe, he noticed something that caused him to do a double take: “a beautiful cascade of faint stars tumbling from the northeast down to the open cluster NGC 1502.” Finding no reference to this striking chain of stars, the good Father realized that he had discovered something that no one had ever noticed before, and all with his simple, inexpensive 7×35 binoculars. He immediately dashed off a letter announcing his find to Walter Scott Houston, Deep-Sky Wonders columnist for Sky & Telescope.

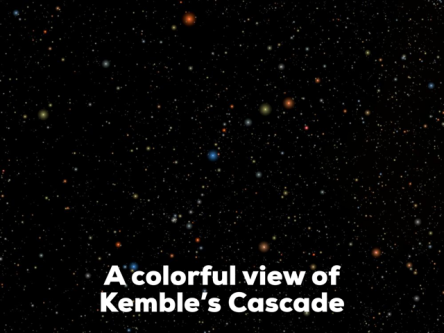

Upon receiving the letter, Houston went outside to take a look for himself. He was “shocked” at what he saw: “there was a totally unexpected gem…a celestial waterfall of dozens of 9th and 10th magnitude stars. Down it went 2 ½” before splashing into NGC 1502.” In the December 1980 issue of Sky & Telescope, Houston wrote a piece about the find and suggested that this delightful little asterism, resembling a tumbling waterfall of stars, be named in honor of its founder and he suggested that it be called “Kemble’s Cascade”. The name has stuck ever since.

Upon receiving the letter, Houston went outside to take a look for himself. He was “shocked” at what he saw: “there was a totally unexpected gem…a celestial waterfall of dozens of 9th and 10th magnitude stars. Down it went 2 ½” before splashing into NGC 1502.” In the December 1980 issue of Sky & Telescope, Houston wrote a piece about the find and suggested that this delightful little asterism, resembling a tumbling waterfall of stars, be named in honor of its founder and he suggested that it be called “Kemble’s Cascade”. The name has stuck ever since.

HOW TO FIND IT AND WHAT YOU WILL SEE

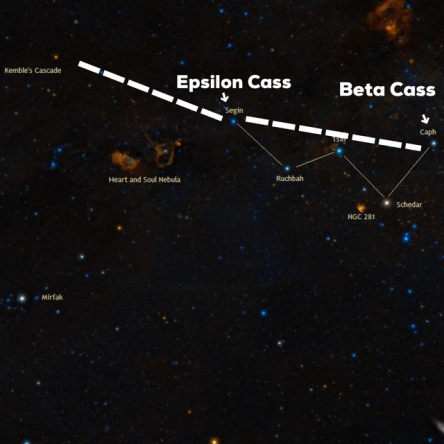

Step outside on any clear, dark night this month and face north. Although Kemble’s Cascade is located in Camelopardalis, the majority of its stars are so faint that you are likely to only see four of its stars, and that is only possible if you happen to be observing from a dark sky location, free of most light pollution. Since most of us live under skies with some degree of light pollution, what are we to do? Fortunately, we have the stars of Cassiopeia to be our guide, which can be readily seen even on bright moonlit nights.

Cassiopeia is the constellation that looks either like the letter M or W, depending on the time of night or time of year that you are observing. Right now, the constellation is standing on its end during the early evening so just go with whichever letter you prefer.

Cassiopeia is the constellation that looks either like the letter M or W, depending on the time of night or time of year that you are observing. Right now, the constellation is standing on its end during the early evening so just go with whichever letter you prefer.

- Find the two stars that form the ends of the constellation. Start at Beta Cassiopeiae (Caph) and draw an imaginary line to Epsilon Cassiopeiae (Segin).

- Next, extend another imaginary line along the same direction and that is roughly equal in length to the first line.

- Scan the area where the line terminates with your binoculars and you should find Kemble’s Cascade. It will appear as a diagonal string of 15 to 25 stars (depending on the size of the binoculars you are using) that is about 2.5 degrees long, which is equal to 5 full moons lined up in a row (this is why the Cascade is best seen with the wider field of view provide by binoculars rather than the more restricted FOV of a telescope).

If you follow the tumbling cascade from its head then about midway along its length, the flow seems to encounter a bright “boulder” star, and then takes a slight jog to the west, continuing on in its southerly journey. This flowing stream of stellar light finally terminates in a fuzzy patch of light (you might need to use averted vision to see it), this fuzzy light is the open star cluster NGC 1502. So, while the stars of Kemble’s Cascade are not physically related, the stars of NGC 1502 are. We don’t have a very accurate estimate of its distance, but it is almost certainly a few thousand light years away. Nor do we have an accurate age estimate for the cluster but, judging by the fact that it contains a number of stars that are much bigger, brighter, and hotter than the Sun, stars that live for only a few tens of millions of years instead of the billions of years for stars like our own Sun, the cluster is probably relatively young at just a few millions of years old.

That’s all for now but I just want to reiterate to you that there are many splendid sights in our night sky that are easily accessed with nothing more than a simple pair of binoculars. Check with your local library or bookstore in order to find a good binocular guidebook to the night sky. Two titles I can suggest right off hand are, “Discover the Night Sky Through Binoculars” by Stephen Tonkin and “Touring the Universe Through Binoculars” by Philip S. Harrington.

That’s all for now but I just want to reiterate to you that there are many splendid sights in our night sky that are easily accessed with nothing more than a simple pair of binoculars. Check with your local library or bookstore in order to find a good binocular guidebook to the night sky. Two titles I can suggest right off hand are, “Discover the Night Sky Through Binoculars” by Stephen Tonkin and “Touring the Universe Through Binoculars” by Philip S. Harrington.

Clear skies and keep looking up in both awe and wonder!