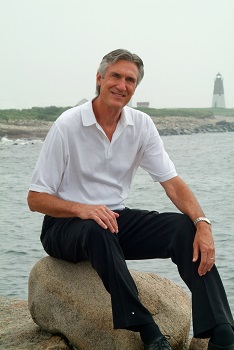

Bowen names classroom in honor of alum Sam Perroni

The University of Arkansas at Little Rock William H. Bowen School of Law has renamed one of its classrooms in honor of alumnus Sam Perroni.

Perroni is such a legend in the Little Rock legal community that it’s difficult to believe he wasn’t always here. He grew up in Normal, Illinois, and always wanted to be a lawyer.

“Don’t ask me where it came from. No one in my family was a lawyer. I didn’t know any lawyers,” Perroni said.

He first applied to the University of Illinois Law School, but competition was fierce—3,000 applicants vied for 300 spots. Perroni was understandably disappointed when he wasn’t one of the 300.

“I thought ‘Okay then, that’s it,’ and then my wife’s boss had a talk with me about persistence and encouraged me to apply to schools until I got accepted.”

He worked for a small corporation for a year and waited for application periods to open. The University of Arkansas Law School was the first to accept him, but Perroni had misgivings.

“Normal, Illinois, was a college town, and I didn’t want to be in Fayetteville without knowing anyone,” Perroni said. “It’s too difficult to get a job, and I was going to have to work while I was in law school.”

However, he had the option of going to law school part-time in the Little Rock division of the University of Arkansas School of Law, which is now the UA Little Rock William H. Bowen School of Law. He took the leap.

“Best decision I ever made, other than marrying my wife,” he said.

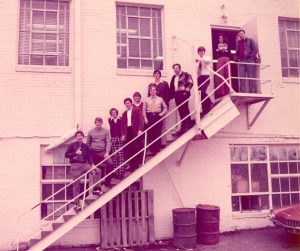

Perroni and his family arrived in Little Rock in 1971 and settled in southwest Little Rock. When registration day came, he went to the university’s main campus, but he couldn’t find the law school building. He had to find the address in the phone book. Then he headed downtown to the corner of Third Street and Broadway.

“I looked everywhere on that corner until I spotted a meager black and white sign on the second floor of Everett’s Glass Shop,” he explains. “And then I thought, ‘what the hell have I done?’”

Perroni stood in the parking lot for a moment and gave himself a pep talk. He decided it didn’t matter what the school looked like if it gave him a good legal education. He went into the glass shop and upstairs to register.

“The student body association president was the first to greet me. He stuck out his hand and said, ‘Welcome to the law school,’” Perroni said.

That personal experience continued during his time as a student. The law school and the law library were both housed on the second floor.

“It was beyond unique. The professors’ doors were always open,” he said. “You could just walk down the hall to ask them questions. We all felt like the professors were interested in us. It was more like a giant family.”

If Perroni needed any other reinforcement, it came when his friend Harold visited. Harold was one of the 300 accepted to the University of Illinois Law School. Harold was surprised at the access Perroni had to his professors. In contrast, Harold was completely on his own.

“It also turned out that Glen Pasvogel, one of my professors, had also been Harold’s legal writing professor,” Perroni said.

As a night student with a family, Perroni worked during the day as a freelance researcher/law clerk.

“None of the attorneys could afford a full-time clerk, so I floated between assignments,” he said. “I researched in the law library and hand-wrote my briefs.”

At some point during law school, Perroni worked for Judge Bill Wilson (who was then in private practice), Jack Holt Jr., Judge Henry Woods (at McMath Letherman & Woods), and Tom Bramhall. He was also taking 15 hours of classes each semester.

“At that time, the ABA didn’t police the schools as strictly,” Perroni said. “I wasn’t the only student who did it, but it let me graduate in three years instead of four.”

The summer he was studying for the bar exam, he was a clerk for the U.S. Attorney’s office. He got that position thanks to his determination, persistence, and freelance experiences.

While his freelance clients couldn’t afford to hire him as an associate, they all wanted to help him succeed. Perroni already had been involved in several high-profile criminal cases, and he liked the work. Everyone told him the best way to be a good criminal defense lawyer was to start as a prosecutor.

Perroni made an appointment to see U.S. Attorney Sonny Dillahunty, who worked out of the post office. At that time, the U.S. Attorney didn’t have a law clerk, and Perroni didn’t have his license yet.

“I walked in and told him I’d work for free.”

A few days later, Dillahunty called him back with an offer of a paying job.

“For the next three months, I got excellent experience, and, when Sonny got permission to hire an Assistant U.S. Attorney, he found me in the library and offered me the job,” Perroni said.

Two years later, Perroni began prosecuting white collar crime cases. Since there was a lot of focus on those cases beginning in 1976, he did little else for the next three years. When he went into private practice, he was the only lawyer who tried to specialize in white collar criminal defense.

“I liked doing them, and I liked that most of my clients could pay,” he said.

Also, because the cases were complex, he didn’t have a heavy caseload. Trials averaged two to four weeks each, so three active cases could mean up to three months in court each year.

While working as an attorney, Perroni returned to law school at night, this time as an adjunct professor.

“I felt that teaching in the law school was the highest calling in the profession. You’re molding future lawyers, and you can make good ones or bad based on what you teach them,” Perroni said. “I see my former students and the lawyers they’ve become, and I’m proud to have had a hand in it.”

Nowadays, Perroni and his wife of 50 years, Patricia, live in northwest Arkansas to be closer to their family. They have a son, daughter, two grandsons, and a granddaughter. He’s continued researching and writing, but now as an author. His first novel, “Kind Eyes,” is a fictional retelling of Abraham Lincoln’s last case as a criminal defense attorney.

“A lot of people don’t know this, but Lincoln was a very good criminal defense attorney,” Perroni said. “He tried nearly 20 murder cases in his 25-year career in private practice. He really liked it, and he told lots of stories about his cases.”

Perroni just finished work on his second project, an investigation of actress Natalie Wood’s death.

Perroni just finished work on his second project, an investigation of actress Natalie Wood’s death.

“I’ve been investigating it for four years, and I found a lot of new evidence,” he said.

When he’s not at the computer, Perroni can be found at Perroni Field, the Little League practice diamond he built for his grandchildren, complete with concessions, an electronic scoreboard, foul poles, and dugouts.

“Once all the coaches found out, they wanted to use it. Now we have six teams practicing and scrimmaging,” Perroni said. “We have baseball here every night. I work my concession stand when the boys are playing. It’s called Sam’s Shack.”

When asked about his hope for the future of the legal profession, Perroni is guarded.

“My practice revolved around the personal relationships I developed,” Perroni said. “Clients look to their attorney to help them make a decision, and that equals personal contact. That interaction is invaluable, and it builds a trust that you can’t forge through text messages and email. The profession is sacrificing those relationships in the name of speed. It’s troubling, and I hope future students are taught the value of building those relationships. I had a great experience as a student at Bowen. The school gave me a great start on my career. It helped me get to where I am today.”