Dr. Yang Luo-Branch*

I. INTRODUCTION

Many Little Rock residents perceive the area around the University of Arkansas at Little Rock (“UALR”) campus as decayed, dangerous, and threatening to the long-term growth of UALR and the surrounding area of Little Rock. While validating the civic perception, this paper examines the actual crime rate in the area and analyzes the factors that contributed to public disapproval of the area.

Officials from the City of Little Rock and UALR launched a comprehensive revitalization project in 2007. By establishing a “University District,” officials hoped to overcome the lack of economic and population growth in the area surrounding the UALR campus that has developed over the past few decades. The project was initiated based on an official vision for the UALR area announced in 2004. The vision stated the area surrounding the UALR campus would become an “in-town destination” and a “neighborhood-of-choice” by 2014. Eight years after officials announced the revitalization plan to the public, there have been no indications of concrete environmental engineering or construction efforts to meet these goals. This lack of progress may stem from the gigantic scale of the project, in terms of organization, staff, time, financial investment, and the cooperation of many partners and direct contributors. However, to prevent the bad situation from getting worse, the poor image that the residents of the city have developed of the study site needs to be addressed immediately.

This study presents a few simple urban planning and placemaking solutions towards improving urban safety in the area surrounding the UALR campus. Research shows that there are two main factors that directly affect urban safety that can be corrected through environmental design: Crime rate and public fear of crime. This article will focus on both on urban planning and placemaking methods to prevent crime and improve the public’s perceptions of crime in the studied area. The author recommends an “Urban Growth Boundary” to the City of Little Rock to help the study site while promoting sustainable development for the entire metropolitan area of Little Rock.

II. LITERATURE REVIEW

A. Civic Efforts to Revitalize the UALR Campus Area

The study site of the research is the area immediately surrounding the UALR campus, mainly along University Avenue and Asher Avenue. These are two major city transportation arteries on the western and southern boundaries of the UALR campus. The study site significantly grew in the 1960s to 1970s as a destination for residential development, shopping centers, restaurants, automobile stores, and other businesses that chose to locate to this area. UALR also experienced significant growth during this time. As the city continues to expand westward away from downtown, the study site has suffered from blight and deterioration since the 1990s. Today, this area is identified in the University District Revitalization Plan as being a location that residents and visitors of Little Rock view as a “pass-through corridor lined with unsafe and obsolete shopping center ‘strip-malls’ with large expanse of bleak, un-landscaped asphalt parking areas.”[1]

Among all the efforts the City of Little Rock, UALR, and other organizations have made to redevelop this area, there are three substantial projects. The first is the update of the UALR Campus Master Plan initiated in 2004. Although the project focuses on the internal planning of the University campus, it also aims to revitalize the immediate areas surrounding the campus. The plan includes a vision of a University District that was to be realized in 2014, which states,

The University District is a thriving cultural and entertainment destination, regarded throughout the city as a neighborhood of choice—a walkable, in-town district with excellent schools and services, vibrant commercial areas, rich cultural resources, and connections to open space and transit. A mix of single-family and higher-density housing attracts a diverse community, including many UALR faculty and staff who choose to live as well as work in the district.[2]

The second effort was an extension of the first planning project focused on realizing the vision for developing the University District. UALR published three main urban-planning documents on its website: Strategic Plan, Revitalization Plan, and Establishing University Village, with the first two documents created in 2007 and the last document created in 2013. Unfortunately, no noticeable physical changes have been observed and the Vision is far from being realized.

Another recent effort was the proposal to create a Tech Park in the area on an 84.37-acre piece of nearby land. The Tech Park was intended to house a variety of economic-focused projects. Although some city and university officials presented strong arguments on how such an urban infill project would benefit the university and surrounding area as well as the Tech Park itself, a location in downtown Little Rock was chosen instead.

From an urban planning and placemaking perspective, there are four approaches to assist with crime prevention and improve public perception of crime in the studied area. These approaches are valuable for the following reasons:

(i) They can be achieved with fewer people and organizations, less time, and lower costs than the previous three projects;

(ii) They are suggested from a profession-specific point of view, which may not be readily apparent to those not trained in urban planning theory; and

(iii) They can produce noticeable results in a comparatively short period of time.

This study presents a new perspective to revitalizing the study site; that is taking simple and easily achievable steps towards meeting the basic human need for a sense of safety.

B. Urban Safety through Environmental Design

The most prevalent topic in improving urban safety by design is about crime prevention: Crime Prevention through Environmental Design (“CPTED”).[3] The first publication on the relationship between crime and environmental design appeared in Jane Jacob’s The Death and Life of Great American Cities.[4] In the 1970s, the term CPTED was first coined and made known through two pioneers’ books: Schlomo Jeffery’s Crime Prevention through Environmental Design[5] and Oscar Newman’s Defensible Space: Crime Prevention through Urban Design.[6] Today, the International CPTED Association defines CPTED “as a multi-disciplinary approach to deterring criminal behavior through environmental design.”[7]

There are many factors that are controllable through environmental design that can prevent crime, such as the accessibility to a location, density and intensity of human activities in an urban space, the mixed uses of space for different city functions, the integration of land-use, and the vitality of an urban district or neighborhood. For example, low-crime neighborhoods often have narrower, one-way routes that accommodate slow traffic, while high-crime neighborhoods usually provide an easy and quick entry and escape route to the city streets. Neighborhood crime patterns can be changed by modifying the layout of the neighborhood.[8] Three concepts serve as the underlying principles for CPTED:

(i) “Eyes on the Streets” is the natural and spontaneous surveillance that people provide when moving about in an environment, such as in the street, neighborhood, or building;[9]

(ii) “Sense of Territory” means that people defend, respect, and take care of a place that they perceive ownership over;[10] and

(iii) “Broken Window” means that serious social disorder can be prevented by taking care of minor incidences.[11]

Based on these principles, a good CPTED practice is one that is under sufficient formal or informal surveillance during the day, properly lit up at night, as well as structurally and aesthetically maintained.

At the same time, urban safety also takes “fear of crime” into consideration, which is an emotional reaction to perceived physical harm and potential danger in the environment.[12] The sight of physical deterioration and blight in a neighborhood, shopping center, or downtown area triggers individuals’ mental connections with social disorder in the area and themselves being victimized by crime.[13] The sense of safety is one the most basic human needs. Therefore, reducing public fear of crime is just as important at preventing actual crime. The current study focuses on addressing both aspects: preventing crime and eliminating the sense of crime.

Besides improving urban safety through better environmental design, there are two other effective approaches: law enforcement and enhancing social bonds.[14] Through the implementation of new laws and the use of police force, law enforcement has been the most commonly utilized and effective method to prevent crime and the sense of crime. In terms of enhancing social bonds, one example is that an individual that is already at risk to commit a crime may be more likely to do so when they feel isolated from important social networks, such as family and friends.[15] Social bonds are not acknowledged as a crime-reducing factor as often as law enforcement is.

According to 2015 FBI data, Little Rock is the most dangerous city in the United State among cities with a population under 200,000.[16] Social gentrification and segregation in the Little Rock metropolitan area have increased since the mid-1920s and escalated since the 1950s.[17] The next question to be analyzed in this study is whether the UALR campus is truly located in a high crime rate area or if it is merely the public’s perception of the environment that leads them to fear being victimized by crime activities in this area. To answer this question, the next section discusses Little Rock crime distribution patterns.

III. CRIME ANALYSIS

A. Methodology

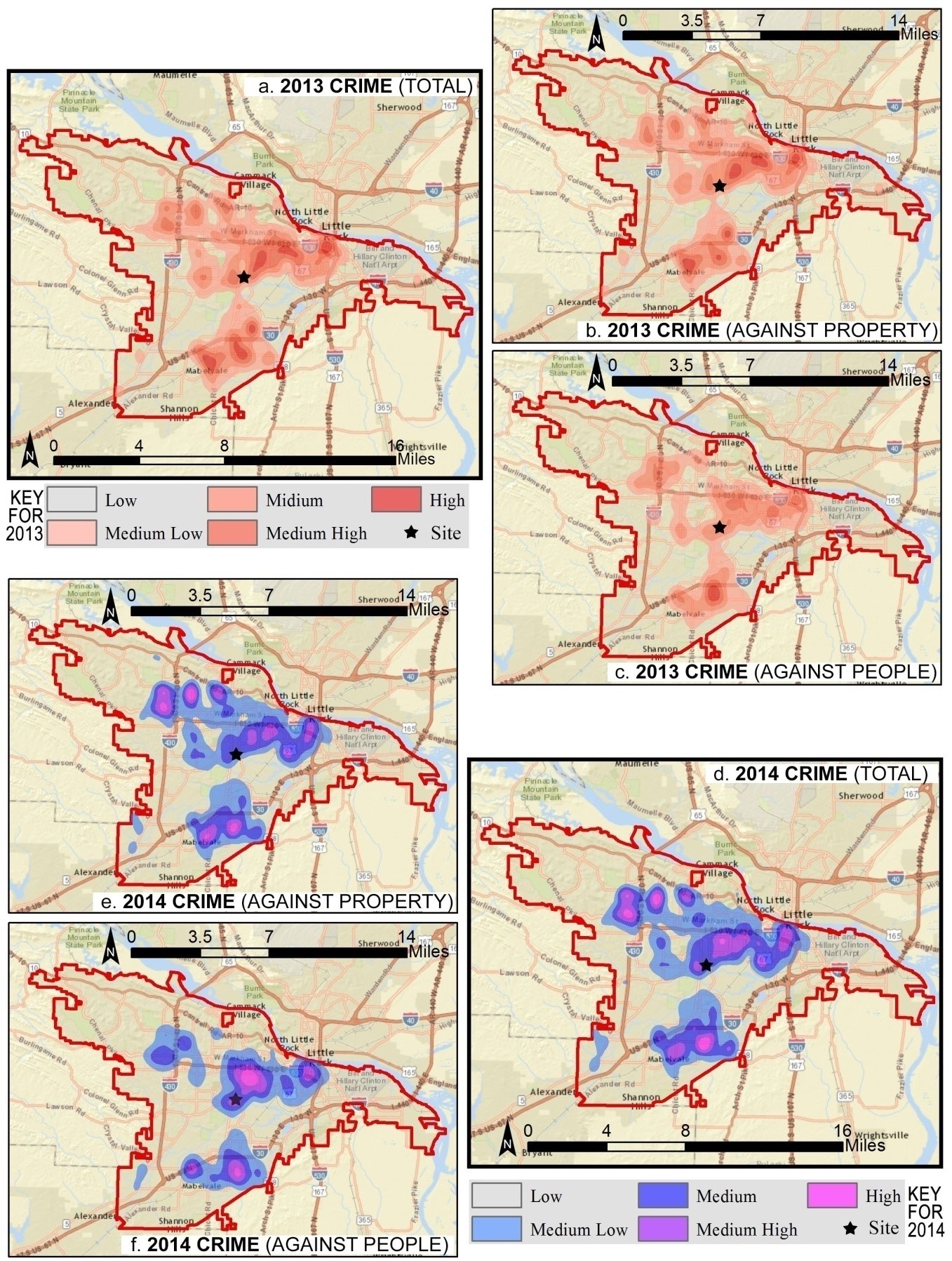

The crime data[18] was collected for the full year from January 1, 2013 to January 1, 2014 and from January 2, 2014 to January 1, 2015. The Little Rock Police Department updates the data weekly with information for each case including crime type, date, time, and location. The types of crime recorded in the database are first-degree battery, robbery, auto theft, commercial and residential burglary, and homicide. There are records of 4411 crime occurrences of these types in 2013 (auto theft 1017, battery 143, commercial burglary 310, homicide 25, residential burglary 2127, and robbery 771) and 4643 in 2014 (auto theft 1196, battery 145, commercial burglary 304, homicide 30, residential burglary 2196, and robbery 751). This data was compiled into a Geographic Information System (GIS) software, ArcGIS (version 10.2.3). Each incidence of crime was assigned a point on the base-map through a geocoding process. Density analysis was conducted with Kernel Density tool in three categories: total crime occurrences, crimes against property (auto theft and burglary), and crimes against people (battery, homicide and robbery).

B. Results

Figure 1 shows the results of the crime distribution/density analysis within the city limit of Little Rock in 2013 and 2014. It is visualized with the Kernel Density tool using “Equal Interval” classification by classifying the gathering degree of the crime location points into five equal degrees. The qualifying of the classification is calculated using “square map units.” In order to make the result more understandable, the five equal degrees are categorized as such: low, medium low, medium, medium-high, and high.

Figure 1 (a through f): The crime density distribution in Little Rock in 2013 and 2014.

C. Finding and Discussion

As shown in Figure 1, the study site is within the medium to medium-high crime rate area for 2013 and 2014. The same pattern is followed by the two crime categories, crimes against property and crimes against people, during this period. Clusters of the crime rate from medium low to high are generally divided into a lower (south) and an upper (north) continuous colorized areas (except for Figure 1-f, because compared to other diagrams, the upper colorized areas are divided into a west and a mid-town-to-downtown regions). The study site is clearly located at the center of the south edge of the upper crime cluster, which spreads along Interstate 630 at its widest section and seizes at Cantrell Road as its northern edge.

Two conclusions can be drawn from the crime analysis based on 2013 and 2014 data: First, the crime rate of the study site is at medium to medium-high level when compared to the rest of the city. The area immediately surrounding the UALR campus suffers not only from the poor image that people do not feel safe there but also from an above-average crime rate, although it is not the most dangerous part of the city. Second, the study site is on the interface between low crime areas and a higher crime rate clustering area.

IV. IMPROVING URBAN SAFETY THROUGH ENVIRONMENTAL DESIGN

Urban safety, as stated above, includes preventing crime and improving the public’s perception of safety. Built environmental design suggestions will be provided to improve urban safety in the study area. Urban planning and placemaking are two professional methods of designing a built environment. They both deal with the physical structures at a regional level, with urban planning mainly focusing on land-use and zoning range from city to neighborhood level, while placemaking emphasizes the more detailed design aspect at the human interaction level in the community.

A. Site Analysis: The Significance of Urban Planning and Importance of Placemaking

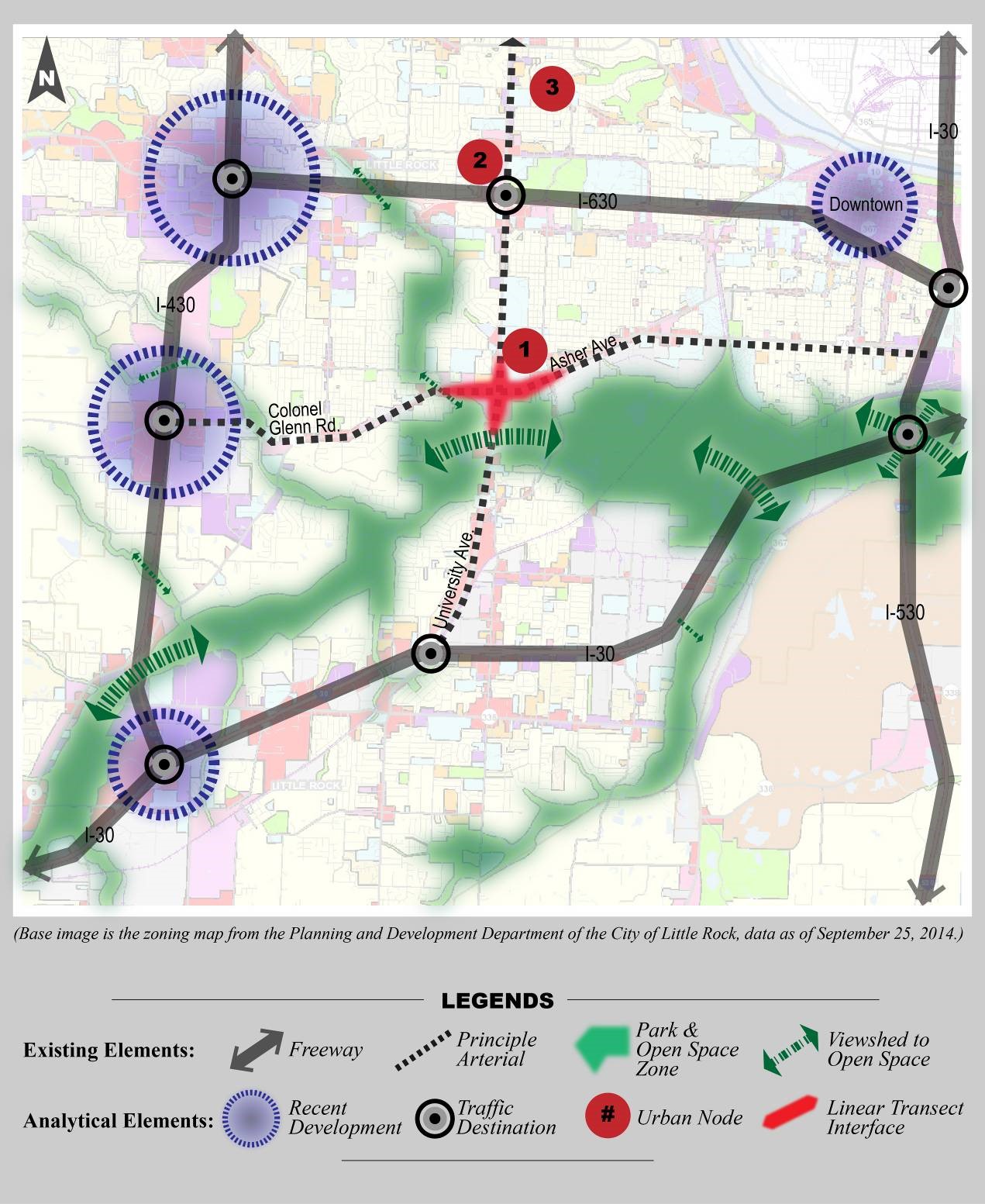

The study site, UALR and its surrounding area (shown in the Figure 2 as the circled number “1”), is at the intersection of Asher Avenue (Colonel Glenn Rd to the west) and University Avenue. The city’s new developments (the blue shaded circles) are strongly shaped by the intersections of the city’s traffic structure, located at the intersections of Interstate Highways. At the inner city (also referred to as mid-town), University Avenue is the biggest north-south city artery, running perpendicular to Interstate-30, Interstate-630 and stretching northward until it meets a city east-west artery, Cantrell Road. Many perceive the major intersections along University Avenue as transportation destinations (shown in Figure 2 as grey and black circles) where people wish to travel across the city expeditiously.

Although University Avenue is frequently used as an urban traffic corridor where people aim to get to the transportation destinations, there are two major urban “nodes” where civic activities take place. These social destinations contribute to slowing down traffic and make University Avenue seem less of a traffic “corridor”[19] than without the nodes. These nodes are the Park Plaza Mall (circled number “2”) and the Heights and Hillcrest Neighborhoods (circled number “3”).

Figure 2: Site analysis about the strategic location of the study area.

The study site is critical for several reasons. First, it is the interface between “general urban” to “urban center” transect.[20] Between these two transects, three factors contribute to the transition of the public’s experiences of the streetscape when they drive North on South University Avenue:

(i) The street width of University Avenue gradually decreases, from 115 feet at south of Asher Avenue to 50 feet wide at north of the Park Plaza Mall;

(ii) The building height and density gradually increases beyond UALR campus area, with more stores, restaurants, and institutions replacing the scene of sparsely located structures of automobile dealerships and gas stations that are more prevalent south of Asher Avenue; and

(iii) University Avenue is on an uphill grade running from the south towards the north, making it much easier for vehicles to remain in a controlled state that allows people to pay more attention while driving.

All three of these factors lead people traveling north on University Avenue to feel the city-life atmosphere becoming more intimate (in spatial scale), busier and more interesting (with businesses and activities), and the need to pay more attention to traffic (because of the uphill driving on narrower streets). These feelings are desirable, as they indicate a sense of place and the vitality in the city. The transition point where this experience begins is the UALR Campus and its surroundings.

The red lines in Figure 2 are marked as urban interface or transitions between different urban experiences introduced by different urban transects. It would be considered proper urban planning and design practice if the transition zones can be made more aesthetically pleasing, functional, and even become additional unique “nodes” on University Avenue. An advantage for the site is the city’s major open-space and park system (shown in Figure 2 as the green dashed box) which runs perpendicular with University Avenue right before the streetscape begins to transform. This detail could be carefully utilized as the buffer of the transition zone. Other similar spots where the green open space meets the highway could be preserved natural zones that provide pleasant natural open views for interstate traffic.

The analysis above indicates the significance of the study site in the urban structure of the metropolitan area of Little Rock. However, the current study is not intended to re-master-plan the site, although the author considers it necessary for the long-term growth of the area. Rather, this study focuses on improving the area through simple and easily completed strategies.

B. Urban Safety Suggestions through Environmental Design

This section gives environmental design suggestions to improve the public’s comfort level and prevent crime in the study area. These suggestions are based on the current condition of the study site and the 2004 Vision of University District. Therefore, these approaches may not be useful when applied to other cases or for a different purpose.

1. Urban Planning: To Promote Natural Surveillance

Natural surveillance is a manifestation of the difference between public space and private space: public space is more physically accessible and visible, while private space limits who can access it and avoids excessive visibility. A semi-public/private space is in between. People intuitively pick up the signals that an environment sends and decide quickly and accurately when it is a good design. A good design practice appropriately matches the intended function of a built environment and its physical characteristics without confusing those who see it; on the other hand, a space develops its own “personality” when it has clearly assigned characteristics.

a. Observation

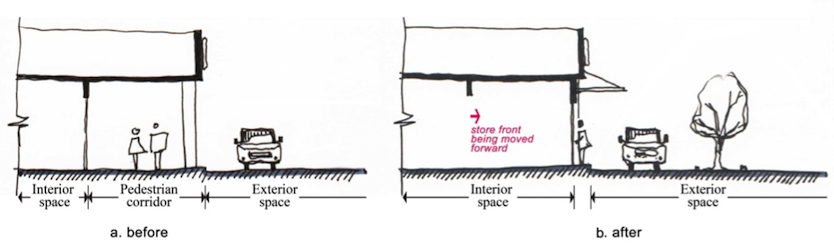

On the south and west of the UALR campus, the architecture style of the shopping centers reflects the typical styling of an American strip shopping mall in the 20th Century: a big parking area in front of the plain-styled retail buildings, which have deep roof awnings supported by columns (see Figure 3). The under-the-awning space, when the usability was high, was intended to provide a safe and shaded pedestrian corridor, and to provide a semi-public space where vehicle accessibility and large volumes of pedestrians were prohibited. Now these shopping centers are experiencing low occupancy rates and these semi-public spaces have become shelters for criminal activity and idling individuals because of the lack of natural surveillance.

Figure 3 (a through d): The pedestrian corridor semi-public space in the shopping centers around the UALR Campus.

b. Solution

Since the occupancy of these shopping centers is low and crime rate is comparatively high in the area, it is advisable to convert these semi-public spaces under the awnings into private space. This can be achieved through architecture modification and adaption: the corridor area in front of each store can be shortened or removed by becoming part of the interior space of the stores (see Figure 4), in order to eliminate the privacy and sheltering usability of the semi-public outdoor space under the awning. When an architectural element is not designed to symbolize long-term stability and usage (like government buildings or courthouses), especially with general retail spaces, it is better to use fixture awnings, which utilize less depth and are not constructed in the same material as the main body of the building (see Figure 5). This will imply flexibility, trendiness, and convenience without emphasizing heaviness.

Figure 4: Reducing the privacy in the semi-public corridor area by expanding the interior space of the store.

Figure 5 (a and b): examples of store fronts with shallower awning covered area.

2. Urban planning: To Enhance Connectivity

Urban compatible and complementary functions need to be connected through physical proximity for mixed-use complexes, pathways at a neighborhood scale, and transit at a greater urban level or above. If safe and convenient connectivity is missing, there are more opportunities for people to experience distractions, higher traveling activation energy, and harm from traffic accidents and criminal activities.[21]

a. Observation

University recreation and student housing are compatible functions for an educational institute and they both exist within the study area. A student apartment complex and a sports and recreation facility are located across Asher Avenue south of the UALR campus (see Figure 6). Although it is possible for students to walk to campus for evening classes from their apartments, the high crime rate around the campus may threaten the students, especially at night (see Figure 7). If the crime rate rises, students may avoid walking although campus is within walking distance. Therefore, providing a safe connectivity between the facilities of the University is vital.

Figure 6 (a and b): UALR facilities that are across Asher Avenue from the main campus.

Figure 7 (a and b): UALR students access university facilities on foot.

b. Solution

Building pedestrian and bicycle-friendly bridges can connect the main campus and the facilities across Asher Avenue. The bridge can be built for public use and should be designed with as much transparency and visibility as possible for it to not become a station for idle behavior and individuals. This approach would not only encourage students to use non-motor transportation safely, but it would also help the University make the statement that it is invested in protecting student safety, especially if the University intends to become the anchor of the in-town destination of the area (see Figure 8).

Figure 8 (a and b): Pedestrian bridges close to educational institute complexes.

3. Placemaking: Reduce Negative Image in Architectural Details

Visual signs can be silent but forceful in environmental communication. When visual signs communicate open, trusting, and welcoming messages, people tend to feel more trusted, invited, and relaxed in those environments. Alternatively, an environment can invoke negative feelings through visual signs of warning, such as severe security devices in an area that is already showing signs of dilapidation. According to environmental psychology, this communicates that the place is unsafe to non-criminals and reinforces anti-social behavior for the crime-prone population.[22]

a. Observation

The study area is in a higher crime rate part of Little Rock. Although it is understandable that the renters of the commercial space will install devices to protect their businesses from property crimes, the following questions should be considered: how effective are these devices and what are the consequences of using them? The use of harsh visual crime prevention devices, such as those shown in Figure 9, reinforces the area’s negative image. From crime data collected over the past two years, it is clear that the crime rates against property and people are still above average. The two images below communicate that the area is dangerous and that the properties are at risk 24 hours per day.

Figure 9 (a and b): Bars and chains as crime prevention devices in the shopping center in the study site.

b. Solution

Appropriate crime prevention devices are necessary because they show that business owners are dedicated to protecting their business. However, the visual communication needs to be subtle and avoid emphasizing anti-social behavior. Examples of effective and thoughtful methods include using “crime-watch” programs, utilizing non-business hour roll-up door (see Figure 10), and having visibility of police staff on site.

Figure 10 (a and b): Crime watching and roll-up doors used as more subtle crime prevention approaches in the neighborhoods and retail spaces.

4. Placemaking: To Promote a Sense of Place through Public Art

The final approach to improving urban safety through environmental design is to establish an identity of a place and to promote civic engagement through the site’s distinctive identities. It is common sense that suspicious people do not wish to stand out and be noticed. In this sense, one way to increase the chance of natural surveillance and reduce crime in an area is to make that area socially active, inviting, and interesting. The identity of a place can be powerfully communicated through visual products such as public art that is authentic to its cultural identity.

a. Observation

In the area surrounding the UALR campus, there are no obvious signs of a local identity as a place. Or worse, there is no plausible identity being perceived, but the area is being label as “dilapidated and high crime.” The lack of civic engagement and pleasant visual products has conveyed the message that this is not a place for people to spend time at.

b. Solution

If the study site is going to establish an identity anchored by the University, the current lack of public art in the area can be seen as a good opportunity for the UALR campus and its neighborhood to start establishing educational public art. For example, in the proposal of University Village, four roundabouts were suggested to slow down the traffic at the section in front of UALR campus on University Avenue.[23] This solution can be refined by adding public art at the middle island to avoid becoming overly-engineered and not pedestrian-friendly (see Figure 12).[24] Other types of public art, such as interactive sculpture, street furniture, and landmarks made from local natural materials (see Figure 13) can be used to increase civic engagement and local cultural awareness while improving the beauty and elegance of the study site. If the public art is consistently themed, the community can effectively communicate its culture to its residents as well as its visitors.

Figure 11: The street round-about solution proposed by the University District.

Figure 12: Example of public arts decorating a street round-about.

- (a)

- (b)

- (c)

Figure 13 (a through c): Examples of public art in the forms of interactive sculpture (a), city outdoor furniture (b) and a natural material sculpture (c).

V. CONCLUSION

This research is a comprehensive study about improving urban safety through environmental design. The research first confirmed the suspicion of many that the UALR campus and its immediate surroundings are situated in a higher crime rate area of Little Rock. According to the Revitalization Report of University District, people also reported that they felt unsafe in the area. Pointing out that the study area is located at an urban transect interface, recommendations were provided from an urban planning and placemaking perspective in order to improve the safety of the area. These recommendations are intended to be simple approaches that involve less labor and financial investment than a more comprehensive revitalization plan.

Additionally, the author considers urban sprawl responsible for the deterioration of the inner city of Little Rock, as exemplified by the study site. Urban sprawl is a type of development that provides short-term gratification for wealthier parts of the population by opening new territory in previously natural or agricultural areas while leaving behind insufficiently used urban space, deteriorated infrastructures, and people that have fewer options. Also, building and maintaining the extended infrastructure on the outskirt of the city needed by urban sprawl is costly. The concept of an “Urban Growth Boundary” confines the spatial expansion of a city and promotes urban infill project and social desegregation. This concept has been proven effective in cities such as Portland, Oregon; Boulder, Colorado; Virginia Beach, Virginia; Lexington, Kentucky; Seattle, Washington; and San Jose, California. Maybe, for its own sustainable development, it is time for Little Rock to reconsider the expansion of its footprint outside of the boundaries of an area already being underutilized.

* Dr. Yang Luo-Branch is the Director of Placemaking and Design for Hot Springs Village, Arkansas. She earned a B.S. in Architecture in China before obtaining a M.A. in Sociology with a minor in Geographic Information Systems from Texas Tech University. In 2013, she obtained a Ph.D. in Land-Use Planning, Management, and Design from Texas Tech University. Her research focuses on community design and development. Before relocating to Hot Springs Village, she taught at the College of Architecture at Texas Tech University.

[1] University District Revitalization Plan, University of Arkansas at Little Rock iv (July 2007), available at https://ualr.edu/universitydistrict/home/strategicplan/.

[2] Partners for Progress: Shaping the Future of the University District, University District Partnership 1 (2007), available at https://ualr.edu/universitydistrict/files/2007/09/2004_Vision_Statement.pdf.

[3] INTERNATIONAL CPTED ASSOCIATION, (May 17, 2015, 7:50 PM), http://www.cpted.net/.

[4] JANE JACOBS, THE LIFE AND DEATH OF GREAT AMERICAN CITIES (1961); Planning Urban Design and Management for Crimeprevention Handbook, European Commission – Directorate-General Justice, Freedom and Security (2007), available at http://www.designforsecurity.org/uploads/files/A01_-_Handbook_English.pdf.

[5] C. RAY JEFFREY, CRIME PREVENTION THROUGH ENVIRONMENTAL DESIGN (1971).

[6] OSCAR NEWMAN, DEFENSIBLE SPACE: CRIME PREVENTION THROUGH URBAN DESIGN (1972).

[7] INTERNATIONAL CPTED ASSOCIATION, supra note 3.

[8] RALPH B. TAYLOR & ADELE V. HARRELL, NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF JUSTICE, PHYSICAL ENVIRONMENT AND CRIME (1996); RONALD E. WILSON, TIMOTHY H. BROWN, & BETH SCHUSTER, Preventing Neighborhood Crime: Geography Matters, 263 NIJ Journal 30-5 (2009).

[9] JACOBS, supra note 3.

[10] JACOBS, supra note 3.

[11] George L. Kelling & James Q. Wilson, Broken Windows: The Police and Neighborhood Safety, ATLANTIC MONTHLY, March 1982, at 29-38.

[12] J. Garofalo, The Fear of Crime: Causes and Consequences, 72 JOURNAL OF CRIMINAL LAW AND CRIMINOLOGY 839-57 (1981); RONALD E. WILSON, TIMOTHY H. BROWN, & BETH SCHUSTER, supra note 8 at 30-35.

[13] J. Gerofalo, supra note 12; Rodney Stark, Deviant Places: A Theory of the Ecology of Crime, 25(4) CRIMINOLOGY 893-910 (1987).

[14] Robert J. Sampson, Stephen W. Raudenbush, & Felton Earls, Neighborhoods and Violent Crime: A Multilevel Study of Collective Efficacy, 277(5328) SCIENCE 918-24 (1997); European Commission, supra note 4.

[15] Matthew Freedman & Emily G. Owens, Low-Income Housing Development and Crime, 70(2) JOURNAL OF URBAN ECONOMICS 115-31 (2011); Robert J. Sampson & Stephen W. Raudenbush, Disorder in Urban Neighborhoods—Does it Lead to Crime?, NIJ JOURNAL, Feb. 2001, at 1-6; Robert J. Sampson, Stephen W. Raudenbush, & Felton Earls, supra note 14.

[16] Kevin Rizzo, Chelsey Goff, & Anneliese Mahoney, Crime in America 2015: Top 10 Most Dangerous Cities Under 200,000, LAW STREET (2015), http://lawstreetmedia.com/blogs/crime/crime-america-2015-top-10-most-dangerous-cities-200000/.

[17] John Kirk & Jess Porter, The Roots of Little Rock’s Segregated Neighborhoods, ARKANSAS TIMES (July 10, 2014), http://www.arktimes.com/arkansas/the-roots-of-little-rocks-segregated-neighborhoods/Content?oid=3383298.

[18] LRPD Crime Map, ARKANSAS ONLINE, http://www.arkansasonline.com/right2know/lrpdreports/.

[19] KEVIN LYNCH, THE IMAGE OF THE CITY (1960).

[20] DANIEL G. PAROLEK, KAREN PAROLEK, & PAUL C. CRAWFORD, FORM-BASED CODES: A GUIDE FOR PLANNERS, URBAN DESIGNERS, MUNICIPALITIES, AND DEVELOPERS (2008).

[21] Patricia L. Brantingham & Paul J. Brantingham, Environment, Routine, and Situation: Toward a Pattern Theory of Crime, 5 ADVANCES IN CRIMINOLOGICAL THEORY 259 (1993).

[22] Thomas J. Bernard & Jeffrey B. Snipes, Theoretical Integration in Criminology, 20 CRIME AND JUSTICE 301 (1996); Robert J. Sampson & Stephen W. Raudenbush supra note 15.

[23] Establishing University Village Report, University of Arkansas at Little Rock 9 (2013), available at https://ualr.edu/universitydistrict/files/2013/06/Establishing-University-Village-Report.pdf

[24] John Massengale & Victor Dover, The Probems with Modern Roundabouts, BETTER CITIES AND TOWNS (January 31, 2014), http://bettercities.net/article/problems-modern-roundabouts-20946