SEEING RED IN A SUPERB STAR

Whenever I give programs on the basics of stargazing I always inform my audience that, through a telescope, they will never see the gorgeous colors that can be found in the pages of glossy astronomy magazines. This news is often met with a few dejected and deflated expressions. I can commiserate, I too was once one of the uninitiated who greatly anticipated a telescope view of the Orion Nebula with all those gaudy colors I had seen in Sky & Telescope or National Geographic. Of course, the harsh reality is that the rods, those light sensitive cells in our retinas that help us to see under low-light conditions, just aren’t sensitive enough to pick out colors in faint objects located many light years away. But, if the object is bright enough we can indeed pick out colors, and stars -being inherently bright objects to begin with- are good examples of nighttime objects in which we can discern a range of colorful hues.

The common assumption is that all stars are white but if you look closer you will begin to pick out some that are blue, white, yellow, or red. Star colors are a function of their surface temperatures with blue stars being the hottest and red stars the coolest. I want to direct your attention to the northern portion of the spring night sky where we can see a rather rare type of red star that goes by the name of Y Canum Venaticorum (Cay-num Vena-tic-orum) or, YCVn for short.

WHEN AND WHERE TO LOOK

FINDING Y CANUM VENATICORUM (YCVN)

YCVn is found within the borders of a constellation known as Canes Venatici (Kay-knees Ven-uh-tee-see). This constellation is not one of our ancient star patterns as it was first introduced in 1687 by Polish astronomer Johannnes Hevelius. It is composed of only two faint stars which are said to represent the hunting dogs of Bootes (Bow-oh-tees) the Herdsman, who is positioned nearby and whose alpha star is the very bright and conspicuous Arcturus.

Canes Venatici is located just under the handle of the Big Dipper. Make a fist and hold it out at arm’s length, the constellation is one fist’s width away and beneath the middle section of the Dipper.

Canes Venatici is located just under the handle of the Big Dipper. Make a fist and hold it out at arm’s length, the constellation is one fist’s width away and beneath the middle section of the Dipper.

There are not too many visible stars in this part of the sky and the two brightest are Cor Caroli (Core Ka-roll-ee), with an apparent magnitude of 2.89, and Chara, with an apparent magnitude of 4.26; the two stars each represent the hunting dogs. As a side note, Cor Caroli means “the heart of Charles” and was named in honor of King Charles I of England who had his head lopped off at the end of the English Civil War. A small telescope will reveal Cor Caroli as a lovely double star. Other telescope treats in Canes Venatici include a globular cluster of stars and a few galaxies.

Now, to find YCVn we are going to draw an imaginary line between Cor Caroli and the star Megrez (meg-rez), which is the star marking where the handle of the Dipper joins the bowl. As we extend that line out from Cor Caroli towards Megrez we will find YCVn about one third of the way. You will know it once you find it as, with optical aid, it is one of the reddest of all stars. My suggestion is to use binoculars at first and then follow up with a telescope view if you have one (small backyard telescopes can now be checked out from various branches of the Central Arkansas Library System provided you are a card-carrying patron).

WHAT YOU ARE SEEING

Y Canes Venaticorum is a a variable star located some 1045 light years away. As the name suggests, variable stars are stars whose brightness changes over a given period. The mechanisms that bring about these changes are various and may be due to factors either intrinsic or extrinsic to the star.

For example, some stars are variable because they are swelling and shrinking in size due to physical changes going on inside them (an intrinsic factor) while others may vary because another star is eclipsing them (an extrinsic factor). The letter ‘Y’ in YCVn is a classification code signifying its status as a variable star. Among variable stars we can place YCVn within the sub-category of “semi-regular” variable stars, these are geriatric stars nearing the end of their lives and whose light output shows appreciable periodicity which can range anywhere from 80 to 1000 days. YCVn changes its brightness over a very rough period of 160 days with a change in magnitude of +4.8 (its brightest) to +6.3 (its dimmest).

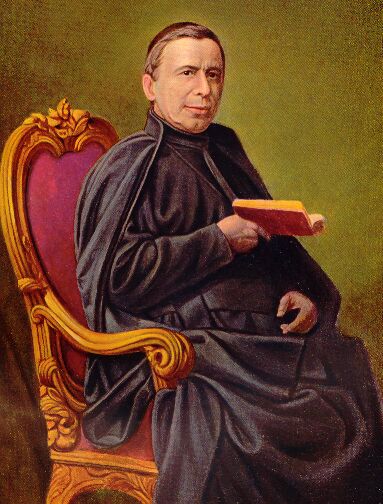

It’s the intensity of the red color (best seen with a small telescope) that makes that makes YCVn such a splendid object for viewing. Being such a beautiful star to observe you would think that YCVn deserves a name with just a bit more cachet. And it has one: “La Superba”.  So named by Father Pietro Angelo Secchi (1818-1878), Jesuit priest, astronomer, and director of the Roman College observatory (now known as the Pontifical Gregorian University). Father Secchi was a pioneer of the then new science of astronomical spectroscopy and one of the founders of modern day astrophysics. He was so taken with the beauty of the spectra of YCVn (the rainbow of colors you get when you tease apart starlight with a prism to learn what the star is made of) and of the star itself that he gave it the name that many amateur astronomers know it by today.

So named by Father Pietro Angelo Secchi (1818-1878), Jesuit priest, astronomer, and director of the Roman College observatory (now known as the Pontifical Gregorian University). Father Secchi was a pioneer of the then new science of astronomical spectroscopy and one of the founders of modern day astrophysics. He was so taken with the beauty of the spectra of YCVn (the rainbow of colors you get when you tease apart starlight with a prism to learn what the star is made of) and of the star itself that he gave it the name that many amateur astronomers know it by today.

But why is La Superba so red? Well, that takes a little explaining but it is a fascinating story so bear with me.

In addition to being a semi-regular variable, La Superba is also a red giant, a geriatric star, highly evolved, and nearing the end of its life. Now, red giants are not at all uncommon, we can see them in the form of stars such as Betelgeuse in Orion, Aldebaran in Taurus, and Antares in Scorpius. What makes La Superba so rare is that it is also what is known as a “carbon star”. Carbon stars are a relatively short stage in the death process of stars that were once very much like our own Sun and catching them in this brief phase of their existence is why they are so rare.

For much of a star’s life they happily fuse hydrogen within their super-hot cores into the element helium. Eventually the hydrogen runs out and when it does the now elderly star’s core compresses and gets hot enough to where it can now begin fusing all that helium it has been storing up into carbon.

Convection currents within the star now begins to dredge some of this carbon up from the interior and delivers it to the star’s outer layers. All of this carbon soot in the star’s outer atmosphere is very good at scattering the bluer portions of the starlight and only allowing the redder portions to pass through the carbon ash before it finally reaches our eyes and triggering a response in our brain that then becomes verbalized as something like “ooooooooh, ahhhhhhhh!”.

As the core of La Superba shrinks and gets hotter it causes the outer layers of the star to swell and cool, making it a much less dense object than, say, the Sun. It is estimated to have a surface temperature of around 5000 degrees Fahrenheit (our Sun, still in its prime, has a surface temperature of about 10,000 degrees Fahrenheit) while its tenuous outer layers would extend all the way out to the orbit of Mars if you were to replace the Sun with La Superba.

But La Superba still has one last hurrah before all is said and done. Thousands of years from now, after you and I are long gone to appreciate it, La Superba will likely transform itself into something even more wondrous: a planetary nebula. While having nothing to do with planets these kinds of nebulas are like gossamer shrouds of glowing gas that clothe the corpse of dead Sun-like stars. As the death process continues stars like La Superba will shed away their outer layers until the finally expose the central core as a white dwarf star. The intense radiation from the now exposed core will excite the atoms that make up the shrouds of the dead star, causing them to fluoresce like gas inside a neon light bulb. If anyone is still around on the planet Earth they can look at with their telescopes and “ooooooooh and ahhhhhhhh” at La Superba for a whole new reason.