There’s a common misconception that in order to see the wonders of the cosmos, you must own a telescope. Not true! There are many wonders overhead that you can see with just your unaided eye: the moon, 5 bright planets, eclipses, stars, constellations, the Milky Way, and even the Andromeda Galaxy located some 2.5 million light years away. Meteor showers are another celestial spectacle that can be readily seen naked eye and this month’s Perseid Meteor Shower is one of the year’s best.

There’s a common misconception that in order to see the wonders of the cosmos, you must own a telescope. Not true! There are many wonders overhead that you can see with just your unaided eye: the moon, 5 bright planets, eclipses, stars, constellations, the Milky Way, and even the Andromeda Galaxy located some 2.5 million light years away. Meteor showers are another celestial spectacle that can be readily seen naked eye and this month’s Perseid Meteor Shower is one of the year’s best.

WHAT ARE METEOR SHOWERS?

I can’t even begin to tell you the number of times that I have been at a public star party when, from out of nowhere, a streak of light blazes across the sky. All of sudden, folks in the crowd who were lucky enough to see it, begin to exclaim things like: “Oh wow, did you see that!” “Look, look, look, a shooting star!” or “Oh. My. God!” For a fleeting second, we all experienced that primal feeling of awe and wonder with the night sky, that same awe and wonder that our ancestors have experienced for thousands of years. To me, such moments are priceless and to be cherished.

I can’t even begin to tell you the number of times that I have been at a public star party when, from out of nowhere, a streak of light blazes across the sky. All of sudden, folks in the crowd who were lucky enough to see it, begin to exclaim things like: “Oh wow, did you see that!” “Look, look, look, a shooting star!” or “Oh. My. God!” For a fleeting second, we all experienced that primal feeling of awe and wonder with the night sky, that same awe and wonder that our ancestors have experienced for thousands of years. To me, such moments are priceless and to be cherished.

But what are meteors? Why do they make glowing streaks across the sky, lasting for only a few seconds? Are they really falling stars?

Well, no they are not stars. The stars that you see in the night sky are bigger, brighter, and much further away than our own Sun (which is 865,370 miles in diameter and located some 93 million miles from the Earth). If you ever see a star falling in our sky, something has gone horribly wrong with gravity and WE ARE ALL GOING TO DIE!

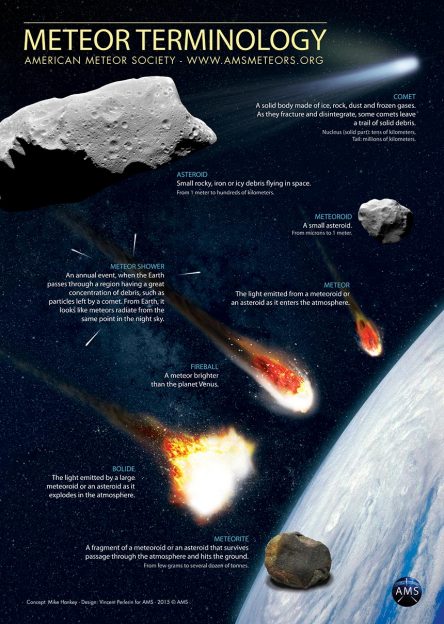

You may be surprised to learn that the vast majority of the meteors that you see are produced by tiny little objects known as “meteoroids”. Meteoroids range in size from particles the size of dust grains to objects that are around 10 meters across, anything bigger, we call an asteroid. On average, the glowing streak that you see in the sky is produced by a meteoroid no bigger than a large grain of sand. Let’s do a recap on some terminology: a “meteoroid” is space debris that ranges in size from dust grains to boulder size, “asteroids” are rocky objects bigger than boulders, and “meteors” are the glowing streaks of light you see in our atmosphere. Sometimes, pieces of larger space rocks survive their entry into the Earth’s atmosphere, if they make it to the ground, we call them “meteorites”.

You may be surprised to learn that the vast majority of the meteors that you see are produced by tiny little objects known as “meteoroids”. Meteoroids range in size from particles the size of dust grains to objects that are around 10 meters across, anything bigger, we call an asteroid. On average, the glowing streak that you see in the sky is produced by a meteoroid no bigger than a large grain of sand. Let’s do a recap on some terminology: a “meteoroid” is space debris that ranges in size from dust grains to boulder size, “asteroids” are rocky objects bigger than boulders, and “meteors” are the glowing streaks of light you see in our atmosphere. Sometimes, pieces of larger space rocks survive their entry into the Earth’s atmosphere, if they make it to the ground, we call them “meteorites”.

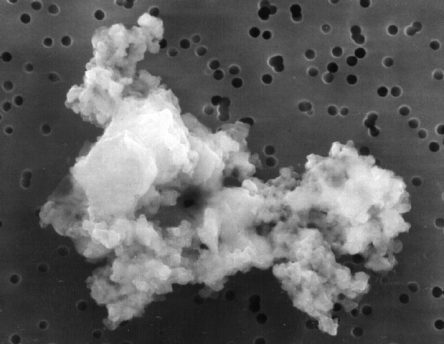

Meteoroids are small bits of interplanetary debris in the form of silicate rocks (silicon and oxygen) or metallic flakes (nickel and iron). They are widespread throughout the solar system and there several different mechanisms by which they are formed. Despite what some science fiction movies would have you believe, the asteroid belt, the reservoir for the majority of the solar system’s space rocks, is not a very crowded place. Lying 329 to 478 million km away, in between the orbits Mars and Jupiter, the asteroid belt is occupied by an estimated 200 asteroids that are over 100 km in diameter, perhaps as many as 2 million that are over 1 km in diameter, and many millions more that are smaller. But there is a lot of volume within the main belt and, on average, asteroids are separated from one another by about 966,000 km. So, while collisions are rare, they do occur and when they do, the rocks shatter. The force of the collision can send the debris, and even the asteroids themselves, heading out of the belt and into the inner parts of the solar system. Occasionally, some of this stuff will collide with the Earth and become visible as a meteor.

The majority of our meteor showers owe their origins to comets, those dirty snowballs from the outer edges of the solar system. Every now and again, a comet from out upon the fringes of our solar neighborhood, has its normal orbit perturbed, and it then finds itself plunging inwards towards the Sun. As the comet gets closer to the Sun, its ices begin to sublimate, that is, they transition from a solid to a gas without an intermediate liquid stage. As comets begin to vent gases into space, they also begin to shed tons of silicate rich dust. It’s the gases and dust that form a comet’s distinctive coma and tail. The trails of dust debris that a comet leaves in its wake may be millions of km long and may persist for centuries. If the dust trail intersects the Earth’s orbit, then we see a meteor shower whenever we plow through it on an annual basis. The Perseid Meteor Shower is the product of Comet Swift-Tuttle, which passes through the inner solar system once every 133 years or so. It last came through in December of 1992.

The majority of our meteor showers owe their origins to comets, those dirty snowballs from the outer edges of the solar system. Every now and again, a comet from out upon the fringes of our solar neighborhood, has its normal orbit perturbed, and it then finds itself plunging inwards towards the Sun. As the comet gets closer to the Sun, its ices begin to sublimate, that is, they transition from a solid to a gas without an intermediate liquid stage. As comets begin to vent gases into space, they also begin to shed tons of silicate rich dust. It’s the gases and dust that form a comet’s distinctive coma and tail. The trails of dust debris that a comet leaves in its wake may be millions of km long and may persist for centuries. If the dust trail intersects the Earth’s orbit, then we see a meteor shower whenever we plow through it on an annual basis. The Perseid Meteor Shower is the product of Comet Swift-Tuttle, which passes through the inner solar system once every 133 years or so. It last came through in December of 1992.

Yet another source on interplanetary debris may actually originate from planets and their moons. Whenever a large space rock impacts a terrestrial planet or moon, it can excavate a large crater and throw a substantial amount of debris into the atmosphere. Sometimes, the force of the impact is so great, that this debris can get hurled away with enough energy that it can achieve escape velocity. Eventually, this debris may collide with another planet or moon. We have actually found meteorites here on Earth that had their origins with the Moon and Mars. I am the proud owner of a fragment of a lunar meteorite that was collected in the Sahara Desert.

But if Perseid meteoroids are no bigger than a grain of sand or rice, then how can they be so bright? The answer is, physics. A sand grain-sized meteoroid may not have a lot of mass but, out in space, it is traveling at very high speeds. Perseid meteoroids are traveling at 132,000 mph. Zoom-zoom! At those velocities, the meteoroids have a lot kinetic energy, the energy they derive from their motion. The thing about kinetic energy is that it can be transferred to other objects and even converted into other kinds of energy. When a sand grain-sized meteoroid, traveling at 132,000 mph out in the vacuum of space, suddenly slams into the Earth’s atmosphere, it transfers that kinetic energy to the atoms and molecules that make up our air. It’s violent encounter with the atmosphere flash heats the air molecules out ahead of the meteoroid’s direction of travel, raising their temperature to thousands of degrees (that kinetic energy has been transferred to the air molecules). This superheated air then glows for a brief second or two (the kinetic energy has now been converted to heat energy), and it is that glowing air that we call a meteor. In the process, the meteoroid vaporizes.

But if Perseid meteoroids are no bigger than a grain of sand or rice, then how can they be so bright? The answer is, physics. A sand grain-sized meteoroid may not have a lot of mass but, out in space, it is traveling at very high speeds. Perseid meteoroids are traveling at 132,000 mph. Zoom-zoom! At those velocities, the meteoroids have a lot kinetic energy, the energy they derive from their motion. The thing about kinetic energy is that it can be transferred to other objects and even converted into other kinds of energy. When a sand grain-sized meteoroid, traveling at 132,000 mph out in the vacuum of space, suddenly slams into the Earth’s atmosphere, it transfers that kinetic energy to the atoms and molecules that make up our air. It’s violent encounter with the atmosphere flash heats the air molecules out ahead of the meteoroid’s direction of travel, raising their temperature to thousands of degrees (that kinetic energy has been transferred to the air molecules). This superheated air then glows for a brief second or two (the kinetic energy has now been converted to heat energy), and it is that glowing air that we call a meteor. In the process, the meteoroid vaporizes.

HOW, WHEN, AND WHERE TO SEE THE PERSEID METEOR SHOWER

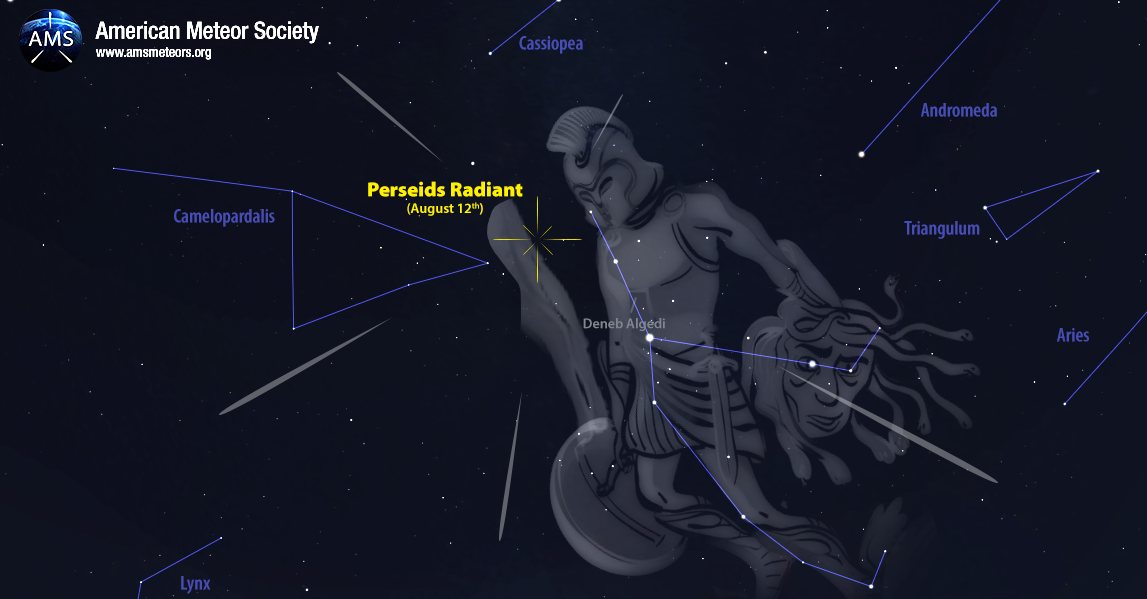

The meteoroid stream from Comet Swift-Tuttle is so broad, that it takes the Earth several weeks to pass through it. You can begin seeing them from around July 14 to August 24. However, the Earth only moves through the densest portions of the stream during the early morning hours (like, a few hours before sunrise) on August 11, 12, and 13, these are the peak times. People often ask me why it is that meteor showers like the Perseids are only at their best during the wee hours of the morning. Most are indeed best seen during the hours before dawn, but not all. The reason why early morning is showtime for most meteor showers has to do with the radiant. If you trace back all of the meteors that you see to their point of origin upon the sky, you would find that they all seem to radiate from one small area upon the sky: the radiant. Astronomers name the meteor shower based upon the constellation or star that the radiant appears to be in. In this case, the meteors all seem to originate from within the constellation of Perseus, the hero of Greek mythology who lopped off the head of the Gorgon sister, Medusa. Just keep in mind that the stars of Perseus are located at various distances from the Earth, but they are all many trillions of miles away. But those meteor streaks that you see are about 60 miles overhead.

The meteoroid stream from Comet Swift-Tuttle is so broad, that it takes the Earth several weeks to pass through it. You can begin seeing them from around July 14 to August 24. However, the Earth only moves through the densest portions of the stream during the early morning hours (like, a few hours before sunrise) on August 11, 12, and 13, these are the peak times. People often ask me why it is that meteor showers like the Perseids are only at their best during the wee hours of the morning. Most are indeed best seen during the hours before dawn, but not all. The reason why early morning is showtime for most meteor showers has to do with the radiant. If you trace back all of the meteors that you see to their point of origin upon the sky, you would find that they all seem to radiate from one small area upon the sky: the radiant. Astronomers name the meteor shower based upon the constellation or star that the radiant appears to be in. In this case, the meteors all seem to originate from within the constellation of Perseus, the hero of Greek mythology who lopped off the head of the Gorgon sister, Medusa. Just keep in mind that the stars of Perseus are located at various distances from the Earth, but they are all many trillions of miles away. But those meteor streaks that you see are about 60 miles overhead.

At this time of the year, the constellation of Perseus does not rise until late evening and does not reach its highest point upon the sky until after midnight. While the radiant is low upon the sky during the evening hours, it is still possible to see Perseid meteors, but you won’t see the most until the hours before sunrise. The radiant is just an indicator as to where the meteor stream is out in space. Remember, the Earth is always moving in two different ways, it is both rotating upon its axis while also moving in its orbit around the Sun. As the Earth rotates upon its axis, it is during the morning hours that the side of the planet you are on is now also facing towards our direction of travel around the Sun. It’s kind of like looking outside the windshield of your car while driving in a snowstorm. During the morning hours before sunrise, the sky overhead Is like your windshield and those meteoroids are like the snowflakes. During the early evening, the sky overhead is like looking out the rear window of your car. At this time, the meteoroids are having to catch up to the Earth before making a bright display in the sky and we see fewer of them. It’s only during the morning hours, as we are plowing through the stream, while facing it head on, that we see the most meteors.

Every meteor shower comes with a predicted hourly rate during the peak times. With the Perseids, you will often see numbers like “100 meteors or more per hour”. Take this with a hefty grain of comet dust. These numbers are idealized, and they have the built-in assumption that you are observing from a site with pristine dark skies and that the radiant is directly overhead. Pristine dark skies are harder and harder to come by these days as we continually light up our nighttime environment in very inappropriate ways. But the real clincher here is that, from our latitude here in Arkansas, the radiant will never reach a point that is directly overhead. So that is going to lower the hourly rate of meteors a bit. On top of that, this year we have a last quarter moon that is going to interfere with the viewing. It doesn’t take a lot of manmade light, or natural moonlight, to drown out all but the brightest of meteors. After you factor all of this in, it is more reasonable to expect to see as many as 40 or 50 meteors per hour, provided that you are viewing from a good, dark sky site. If you can’t make it out on those peak nights, be aware that you can still see meteors on dates either side of the peak dates, albeit at reduced hourly rates.

As I said at the beginning, you don’t need any special equipment to see a meteor shower, your unaided eyes will do just fine but there are a few tips I can give you to help you get the most out of your viewing experience.

As I said at the beginning, you don’t need any special equipment to see a meteor shower, your unaided eyes will do just fine but there are a few tips I can give you to help you get the most out of your viewing experience.

- I cannot emphasize this enough: get thee to a dark sky site. The darker the better. If you don’t, you will not see very many, if any at all. In order to find a dark sky viewing location, please visit the Arkansas Natural Sky Association’s website where you will find a list of suggested sites around the state: https://darkskyarkansas.org Whichever site you choose, make sure that it has as much open sky as possible and is safe for you to view from.

- You can start looking for meteors as soon as it gets dark, but you will not see very many until around midnight. And that’s right around the time that the last quarter moon is rising this month. However, there are some things that you can do. Namely, try blocking the moon out. Position yourself so that the Moon is hidden behind a building, tree line, mountain, or hillside.

- You will need to let your eyes become dark adapted, a process that can take 20 minutes or longer. You will see more of the fainter meteors with dark adapted eyes but if you look into bright light, you are going to destroy your night vision and you will have to start the process over again. Avoid looking at your cell phone, car lights, house lights, bright flashlights etc. In order to see in the dark, use a red LED flashlight since the redder wavelengths of light are less destructive to your night vision. You can also take a regular old flashlight and cover the end in that red plastic film that is used to repair broken taillights.

- Get comfortable. I strongly urge you lay down in a reclining lawn chair or on the ground with a blanket or sleeping bag. If you don’t, you run the risk of straining your neck muscles.

- Take along food and drink as well as some music to keep you entertained during the lulls. And there will be lulls. They might call these things “showers” but do not expect to see meteors falling out of the sky like rain. Be patient. Also, this is Arkansas, pack bug spray.

- It’s always fun to share a meteor shower with friends and loved ones. But if you do, please practice safe social distancing.

NOTE: The Perseids are known for producing very bright meteors and they also have the reputation for producing the very brightest kind of meteor of all: fireballs. Fireballs are as bright, or brighter than the planet Venus, and are produced from meteoroids that are a bit bigger than a sand grain, say, perhaps on the order of pea-sized silicate material. Bill Cooke of NASA’s Meteoroid Environment Office says, “Comet Swift-Tuttle has a huge nucleus–about 26 km in diameter. Most other comets are much smaller, with nuclei only a few kilometers across. As a result, Comet Swift-Tuttle produces a large number of meteoroids, many of which are large enough to produce fireballs.”

And just remember this old meteor watchers saying: “You might see a lot or you might not see many, but if you stay in the house, you won’t see any.”

Get outside, look up!