People have been enthralled by the beauty and mystery of a star-filled sky since, well, since there have been people. In our modern technological age, it can be difficult for us to imagine a time in our history when there were no such things as smartphones, video games, television, the internet, or even books. In ancient times, people often entertained one another through the tradition of oral storytelling, relating stories to an audience with nothing more than the human voice and gestures. Such stories served not only to entertain but to teach the audience about that particular culture’s traditions and values or, it might also be used to explain the world that our ancestors encountered upon a daily basis.

People have been enthralled by the beauty and mystery of a star-filled sky since, well, since there have been people. In our modern technological age, it can be difficult for us to imagine a time in our history when there were no such things as smartphones, video games, television, the internet, or even books. In ancient times, people often entertained one another through the tradition of oral storytelling, relating stories to an audience with nothing more than the human voice and gestures. Such stories served not only to entertain but to teach the audience about that particular culture’s traditions and values or, it might also be used to explain the world that our ancestors encountered upon a daily basis.

Along with the human proclivity for storytelling, there’s also the fact that our brains are wired to seek out patterns from random chaos. In ancient times, with no light pollution, the night sky would have seemed to be overflowing with stars and it wasn’t long before people began to see  amongst all that stellar chaos, patterns that they thought represented a variety of characters from many of their favorite stories. It was at this point that we had constellations. With constellations, the night sky became a storybook. As far as we can tell, throughout history, every single human culture that has ever existed upon the Earth has each had their own constellations and sky lore to go along with them.

amongst all that stellar chaos, patterns that they thought represented a variety of characters from many of their favorite stories. It was at this point that we had constellations. With constellations, the night sky became a storybook. As far as we can tell, throughout history, every single human culture that has ever existed upon the Earth has each had their own constellations and sky lore to go along with them.

I want to tell you about a pattern of stars located beneath Ursa Major, the Great Bear in Greek mythology, that are sometimes known as, “The Three Leaps of the Gazelle”.

CONSTELLATIONS AND ASTERISMS

Today, constellations are used by astronomers to map out the sky in a grid-like pattern in order to help them plot the locations of the stars and various deep sky objects. But with such a rich, diverse array of constellations to choose from, how are astronomers able to mutually agree upon which constellations to use? Enter the International Astronomical Union, a kind of governing body in the field of astronomy.  According to their website, the IAU states that the organization “exists to promote and safeguard the science of astronomy through international cooperation, assign official names and designations to celestial bodies, and liaise with organizations that include amateur astronomers”. The IAU was founded in 1919 and is based in Paris. During the 1920’s the voting members decided to make 88 constellations official, with about 50 of those being derived from the ancient Babylonian and Greco/Roman world.

According to their website, the IAU states that the organization “exists to promote and safeguard the science of astronomy through international cooperation, assign official names and designations to celestial bodies, and liaise with organizations that include amateur astronomers”. The IAU was founded in 1919 and is based in Paris. During the 1920’s the voting members decided to make 88 constellations official, with about 50 of those being derived from the ancient Babylonian and Greco/Roman world.

Some of the more prominent of these official constellations include, Orion, Scorpius, Leo, and Ursa Major. While these are officially sanctioned constellation patterns, with clearly defined borders and star names and catalog numbers, that hasn’t stopped amateur astronomers from either creating or adopting other star patterns in order to help them find their way across the sky. These “unofficial” star patterns are called “asterisms” and they can be made up from stars in one or more of the “official” constellations.  Take for example the seven brightest stars in the official constellation of Ursa Major, they make up one of the most easily recognized patterns of stars in the night sky: the Big Dipper (“The Plough” if you are from the UK or, if you are from Burma, you might see it as a giant prawn). The Three Leaps of the Gazelle is another asterism that can be found in Ursa Major. It just so happens that there are three pairs of stars, positioned quite closely together, that the IAU officially designate as representing the bear’s claws but to Arabs from the Middle Ages, it was said to represent the hoof tracks of a leaping gazelle. Their name for this dainty and rather faint three pairs of stars is “Kafzah al Thiba,” or the “Three Leaps of the Gazelle”. According to Ulugh Beg, a 13th century Arabic Astronomer, who first makes mention of the Three Leaps of the Gazelle, the creature was grazing amongst the stars that, today, we call Leo Minor (the little lion) when Leo, the big lion (whose constellation is found nearby at this time of year) swished its mighty tail across the sky. This startled the gazelle and it bounded away for safety, leaving behind its softly glowing tracks in the sky, still seen by us to this day. Just to the rear of Leo is a misty patch of stars that the IAU officially recognizes as the constellation of Coma Berenices but, in Beg’s day, was recognized by many as the lion’s tufted tail.

Take for example the seven brightest stars in the official constellation of Ursa Major, they make up one of the most easily recognized patterns of stars in the night sky: the Big Dipper (“The Plough” if you are from the UK or, if you are from Burma, you might see it as a giant prawn). The Three Leaps of the Gazelle is another asterism that can be found in Ursa Major. It just so happens that there are three pairs of stars, positioned quite closely together, that the IAU officially designate as representing the bear’s claws but to Arabs from the Middle Ages, it was said to represent the hoof tracks of a leaping gazelle. Their name for this dainty and rather faint three pairs of stars is “Kafzah al Thiba,” or the “Three Leaps of the Gazelle”. According to Ulugh Beg, a 13th century Arabic Astronomer, who first makes mention of the Three Leaps of the Gazelle, the creature was grazing amongst the stars that, today, we call Leo Minor (the little lion) when Leo, the big lion (whose constellation is found nearby at this time of year) swished its mighty tail across the sky. This startled the gazelle and it bounded away for safety, leaving behind its softly glowing tracks in the sky, still seen by us to this day. Just to the rear of Leo is a misty patch of stars that the IAU officially recognizes as the constellation of Coma Berenices but, in Beg’s day, was recognized by many as the lion’s tufted tail.

HOW TO TRACK THE GAZELLE AND WHAT YOU WILL SEE

First off, you need to know that the stars that make up the Three Leaps are not particularly bright and urban light pollution will make them invisible to the unaided eye. To see these six stars, you will need a fairly dark suburban sky. If you need to find a good observing location near you, visit the Arkansas Natural Sky Association website: https://darkskyarkansas.org

First off, you need to know that the stars that make up the Three Leaps are not particularly bright and urban light pollution will make them invisible to the unaided eye. To see these six stars, you will need a fairly dark suburban sky. If you need to find a good observing location near you, visit the Arkansas Natural Sky Association website: https://darkskyarkansas.org

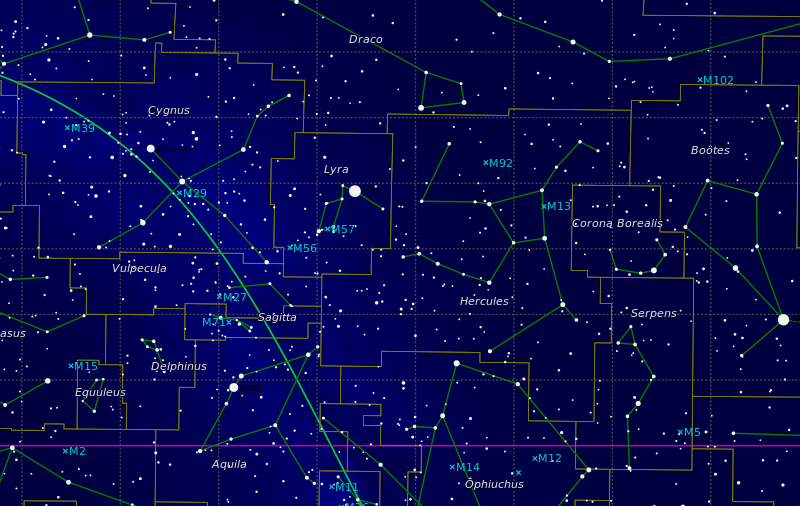

During the month of May, the best way to find the Three Leaps is to first find the Big Dipper. At around 9PM, the dipper can be found by facing NNW and looking up, you’ll see it with the bowl turned upside down.  Next, we are going to locate Leo. Turn towards the left of the dipper’s bowl. The first bright star you come across is Regulus, the heart of Leo, shining with an apparent magnitude of +1.35. The lion hangs upside down in the sky right now but look for a group of six stars, including Regulus, that form a backwards question mark shape (Regulus makes the dot of the question mark). These stars mark out the head, mane, and shoulders of Leo and are actually another asterism known as “the sickle” because it looks a bit like a scythe. Now, make a fist and hold it all the way out at arm’s length. If you go two fist widths back towards the dipper, you will be in the general area of where the Three Leaps can be found. For reference, the dipper’s bowl represents the Great Bear’s hindquarters while the handle is theunusually long tail of the bear. The bear’s legs extend towards Leo and remember that the stars that form the Three Leaps are actually the claws attached to three of the bear’s paws. Consult the accompanying graphic to help guide you.

Next, we are going to locate Leo. Turn towards the left of the dipper’s bowl. The first bright star you come across is Regulus, the heart of Leo, shining with an apparent magnitude of +1.35. The lion hangs upside down in the sky right now but look for a group of six stars, including Regulus, that form a backwards question mark shape (Regulus makes the dot of the question mark). These stars mark out the head, mane, and shoulders of Leo and are actually another asterism known as “the sickle” because it looks a bit like a scythe. Now, make a fist and hold it all the way out at arm’s length. If you go two fist widths back towards the dipper, you will be in the general area of where the Three Leaps can be found. For reference, the dipper’s bowl represents the Great Bear’s hindquarters while the handle is theunusually long tail of the bear. The bear’s legs extend towards Leo and remember that the stars that form the Three Leaps are actually the claws attached to three of the bear’s paws. Consult the accompanying graphic to help guide you.

Moving from the bear’s hind legs to its front legs the three pairs of stars are:

- Alula Borealis and Alula Australis

- Tania Australis and Tania Borealis

- Talitha Australis and Talitha Borealis

The first half of each star name is its proper name while the second half refers to the star’s orientation: Borealis means “north” while Australis means “south”. None of the stars within these three pairs are physically interacting with their companions, it’s purely a line-of-sight effect that they appear so close.

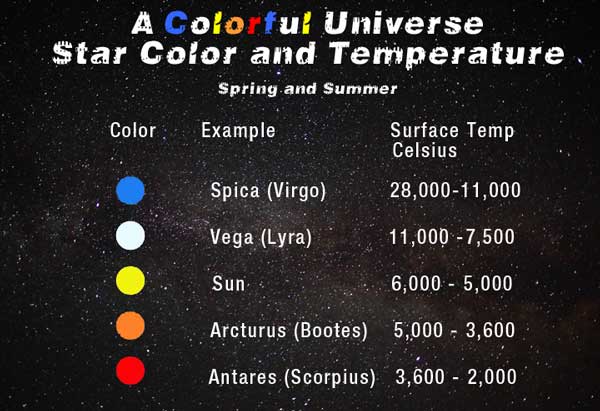

Alula Borealis: This is a giant star that, as it has aged, has expanded its waistline out to about 57 times that of the Sun. That’s a big star and it has a luminosity that is 775 times that of the Sun (a star’s luminosity refers to how much energy it is cranking out per second relative to the Sun’s). The outer layers of the star are a relatively cool 4,000 Kelvin (the Sun is about 5,778 Kelvin), which means that the star is glowing a reddish-orange color. Alula Borealis also has a faint 10th magnitude companion star. In astronomy, the apparent magnitude scale is used to note how bright a star appears when seen with the unaided eye from the Earth. Brighter objects have lower apparent magnitude numbers and dimmer objects have higher numbers. The cutoff limit for naked eye visibility is +6, so you will need a large scope and a magnification of perhaps a 150 to see the companion. Alula is 400 light years away. If you could travel at the speed of light (and, according to the laws of physics, you can’t), it would take you 400 years to get there. If you could travel as fast as NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft, 33,000 mph, it would take you 8,112,835.47 years. Better pack a lunch.

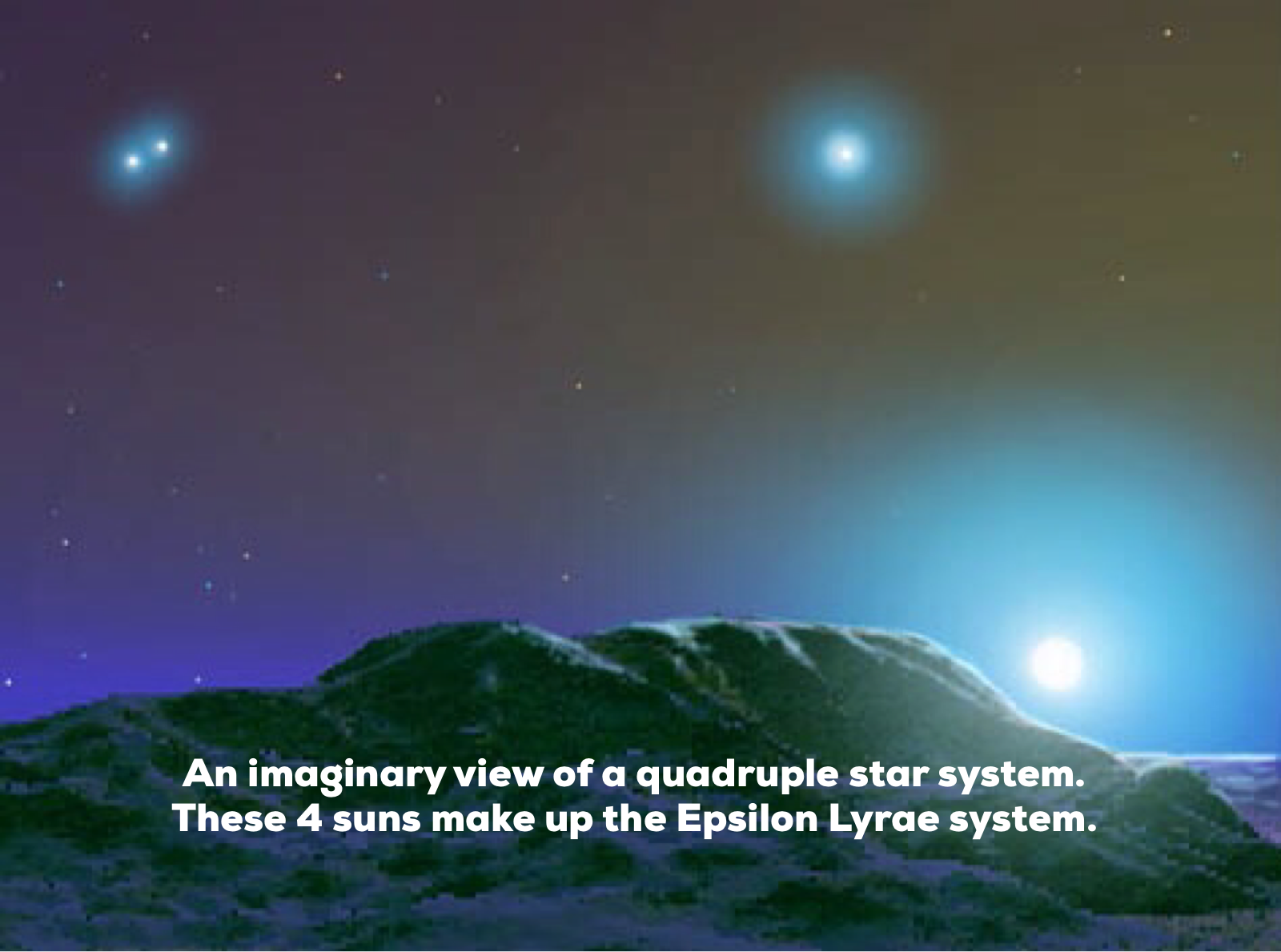

Alula Australis: This is a visual binary star system, the first of its kind ever discovered. Famed German-born British astronomer, Sir William Herschel made this find on May 2, 1780 and, in 1828, it was the first such visual double whose orbit was calculated. Modest-sized telescopes, at high magnification, can split the two stars as a pair of golden hued beauties. It takes about 60 years for the two to orbit around one another. What’s more, we now know that each of the components of this binary system also have companions, which are too close to their primaries to split apart with a backyard telescope. Eat your heart out, Luke Skywalker!

Alula Australis: This is a visual binary star system, the first of its kind ever discovered. Famed German-born British astronomer, Sir William Herschel made this find on May 2, 1780 and, in 1828, it was the first such visual double whose orbit was calculated. Modest-sized telescopes, at high magnification, can split the two stars as a pair of golden hued beauties. It takes about 60 years for the two to orbit around one another. What’s more, we now know that each of the components of this binary system also have companions, which are too close to their primaries to split apart with a backyard telescope. Eat your heart out, Luke Skywalker!

Tania Australis: Another giant, geriatric red star. At 75 times the radius of the Sun, Tania A. has a luminosity of around 1,000 times that of our own local star. It too has a close companion that cannot be split by a telescope and the secondary moves around the primary once every 230 days.

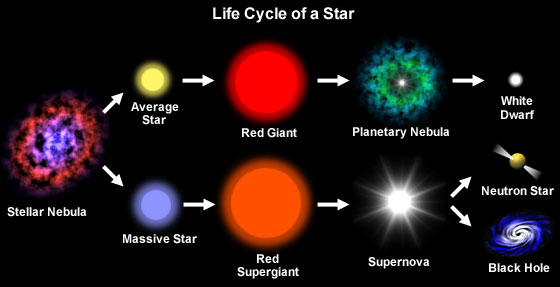

Tania Borealis: This is a star that is evolving into a giant phase. Once a star ceases to fuse hydrogen in its core (the fuel tank is near empty), the core begins to collapse in on itself and it gets hotter. By cranking up the heat in the core’s thermostat, the outer layers of the star begin to swell, and we get a red giant. Tania Borealis is what we call a “subgiant star”, the stage before reaching red giant status. It is among the brightest stars in the Three Leaps.

Talitha Australis: While Tania Borealis is a subgiant based upon the stage of its life, Talitha Australis is a subgiant based upon the color spectrum of the radiation it emits (yes, we have a couple of different subgiant categories and, yes, I know it’s a bit confusing). Based upon its color spectra, this star is a blazingly hot blue-white subgiant with a surface temperature of 10,000 Kelvin (get out the sunblock!). Talitha Australis is actually a multi-star system with two companions orbiting the primary. The companions were discovered back in 1841 and they were much more widely separated than they are now. Because the gap between them and the primary has closed so much since then, you will need a large telescope and high magnifications to split them.

Talitha Australis: While Tania Borealis is a subgiant based upon the stage of its life, Talitha Australis is a subgiant based upon the color spectrum of the radiation it emits (yes, we have a couple of different subgiant categories and, yes, I know it’s a bit confusing). Based upon its color spectra, this star is a blazingly hot blue-white subgiant with a surface temperature of 10,000 Kelvin (get out the sunblock!). Talitha Australis is actually a multi-star system with two companions orbiting the primary. The companions were discovered back in 1841 and they were much more widely separated than they are now. Because the gap between them and the primary has closed so much since then, you will need a large telescope and high magnifications to split them.

Talitha Borealis: There seems to be some confusion regarding the name of this star. Some sources identify as I’ve listed it here while others call it Kappa Ursae Majoris. Apparently, it has an Arabic name as well (ancient Arab astronomers kept the science of astronomy thriving while the west declined into the Dark Ages), “Alkaphrah”, which means, “the leap”. It is another binary star system with the components being to close together to split apart observationally.

That’s all I’ve got for now, but I encourage you get outside at some point this month and see if you can follow the tracks of the celestial gazelle across a starry night sky that is filled with both awe and wonder.